Accreditation Laws are not Violating the American Dream

In light of the SEC re-evaluating accredited investor laws, Anthony Pompliano recently wrote a piece titled Accreditation Laws Are Violating The American Dream And Discriminating Against Millions. In it, he surveys how accreditation laws are keeping everyone but the already-rich from investing in startups. The argument is simple: the wealthy are capturing returns that most of America doesn't have access to and average investors are missing out. Instead, big tech companies are getting dumped on public markets after most of their appreciation has happened. The days of buying Amazon's or Google's IPOs are gone.

Except, it's a bit more complicated.

Who's affected?

The stated reason is that regulators and the government want to protect people from losing all their money... While this sounds good at first glance, if this were really the case, these organizations would shut down lotteries and casinos first.

We'll start with our common ground. Anthony's right that the rules as implemented do not effectively protect the right people, and we do let people gamble their money away. Also, we agree, using wealth as a proxy for intelligence is seriously misguided. We also need to be realistic about what we're talking about and who is actually affected[1]. In reality, as you'll see, it doesn't really matter quite so much, because those affected nearly certainly shouldn't invest in startups. Let me explain.

The median household in America has, depending who you ask, <$20k in savings. We'll cover later why venture is a difficult asset class for the needs of most people and how diversification is necessary to actually reliably realize the historical returns. But even if a top-quartile household wanted to emulate the Yale Endowment portfolio, they'd have barely enough cash for a few direct startup seed investments[2].

In fact, even many accredited investors cannot effectively deploy capital to diversify sufficiently when investing directly in startups. So, the people affected are primarily those who are just barely under the accreditation threshold, willing to invest in high-fee fund/SPV vehicles, and have a high appetite for risk.

Access to returns vs access to variance

Outsized returns only matter if you can actually, reasonably achieve them. When we're talking about outsized returns, we care about risk-adjusted returns, not whether it's possible to hit a home run (i.e. the lottery). This distinction matters because "access to high-variance investments" shouldn't be a desire by itself and is already legal. Even better, there's high-variance alternatives that are liquid, low cost, transparent, and regulated: options.

So, let's look at the startup asset class. Are there reliably obtainable outsized returns? The scale of the injustice varies greatly if venture returns are indeed fantastic and being shielded from average people. If, instead, it wouldn't be a good investment for nearly everyone anyways, then the only argument that holds up is that the government ineffectively keeps people from other bad ways to gamble money.

Further, we need to be careful to not conflate existence of high returns with expectation of high returns. Yes, Uber's seed investors made a lot of money. And yes, there have been VC fund that have done well. We'd also have to admit that there have been lottery tickets that won a lot, Bitcoin made many people multi-millionaires, and you could get rich on penny stocks. Even in the public markets, massive historically outsized returns happen. $10k in Domino's Pizza in January 2010 would be worth almost $400k today, dividend re-invested.

Startups are a bad asset class for most people

As we'll see in a bit, Anthony's characterizations of VC returns are misleading. But even if startups did consistently outperform public market investments, they're still a pretty bad investment for most people.

Public companies have to abide by reporting regulations so that much of their financials are publicly available. Startups do not, and there's incredible information asymmetry, both to prospective investors and within the emerging markets. Investing in startups is hard; harder than picking individual stocks. Does that mean the government should block access, then, and that Accredited Investors are uniquely qualified to make good decisions? Certainly not (see [1:1] again).

Anthony's mention of Yale's endowment implies that you should want to have a high portion of your portfolio exposed to startups. We'll look at how startups tend to return, but first, the structure of the asset is simply not appealing to most people.

There may be a illiquidity premium, but tautologically, that comes at the cost of liquidity. However, most people need liquidity. That's why we even let people loan money to themselves out of their 401k. Of the minority of Americans with meaningful savings, most of those who don't quality for Accredited Investor status need liquidity at hard-to-predict times. This is where venture differs from even gambling at a casino: you're locked out of your money, even if you desperately need it. So, you effectively need to model capital needs 10 years or more into the future.

Further, it's difficult to adequately size startup investments. Most syndicates (charging carry and SPV fees) won't take checks less than $1000-2500. Of the class of Silicon Valley startups that he cites, there were very few small checks taken. And after investment, you can't rebalance your portfolio easily.

The comparison to the Yale endowment ignores that they have a large amount of capital to deploy (thus, per dollar, can do so more efficiently), and their needs are vastly different than most people's. Sure, we'd all like 15% IRR on our portfolio, but they're optimizing for an infinite horizon with predictable cash flows, and can gladly give up liquidity to get access to diversifiers.

Investing in startups directly vs in VC funds

Anthony mentions both investing in VC funds and investing in startups directly. These are quite different. We'll look at both, to see why neither is all that appealing to a upper-middle class investor.

Startup investing: most fail, a few do very well

You already know that startup failure rates are very high. The median dollar invested in early stage startups is not returned. In fact, based on AngelList data of early stage startups with exits, making 10 early stage investments most often returns barely the initial investment after years of no liquidity. Outsized venture returns come from having large winners. Single factor returns won't make a significant difference. So, the investor needs to invest in many startups. Alternatively, they're just playing the startup lottery, where most people lose, and a few people win big.

Most importantly, the average upper-middle class investor wouldn't have access to most early-stage startup rounds. They're unlikely to know about the startups, because by definition, there's little visibility. Most startups prefer to limit the number of investors they have because investor management eats valuable time: strong startups frequently turn down capital that isn't strategic, focusing their raise to be from investors who provide more value than just a check.

Interestingly, early stage startups, with the highest potential returns, can and do take investments from non-accredited investors, but are limited by the number of them (Reg D, Rule 506). So, if someone does have the network and can write a check that a very early stage startup would accept, they could.

After early stages, startups usually raise from larger and larger funds, both for value-add and signaling reasons, and because chasing tiny checks isn't time efficient. Most individuals would have no access to these rounds, and would need to buy and sell on secondary markets. Secondary transactions are often quite illiquid, have very high fees, and prefer large block sales.

So, while it's misleading to act like people would have access to rounds like Uber's seed, they also would have hard time replicating VC returns without just directly investing in a VC fund.

VC funds: deploying large amounts of capital, more diversified, but most do not perform well

Alternatively, the upper-middle class investor could want to invest in VC funds directly. This seems like a more reasonable alternative, and I'd agree should be legal, but is still probably a bad idea. First, let's get out of the way: this means we're not talking about an angel that invested in Uber's seed and made millions.

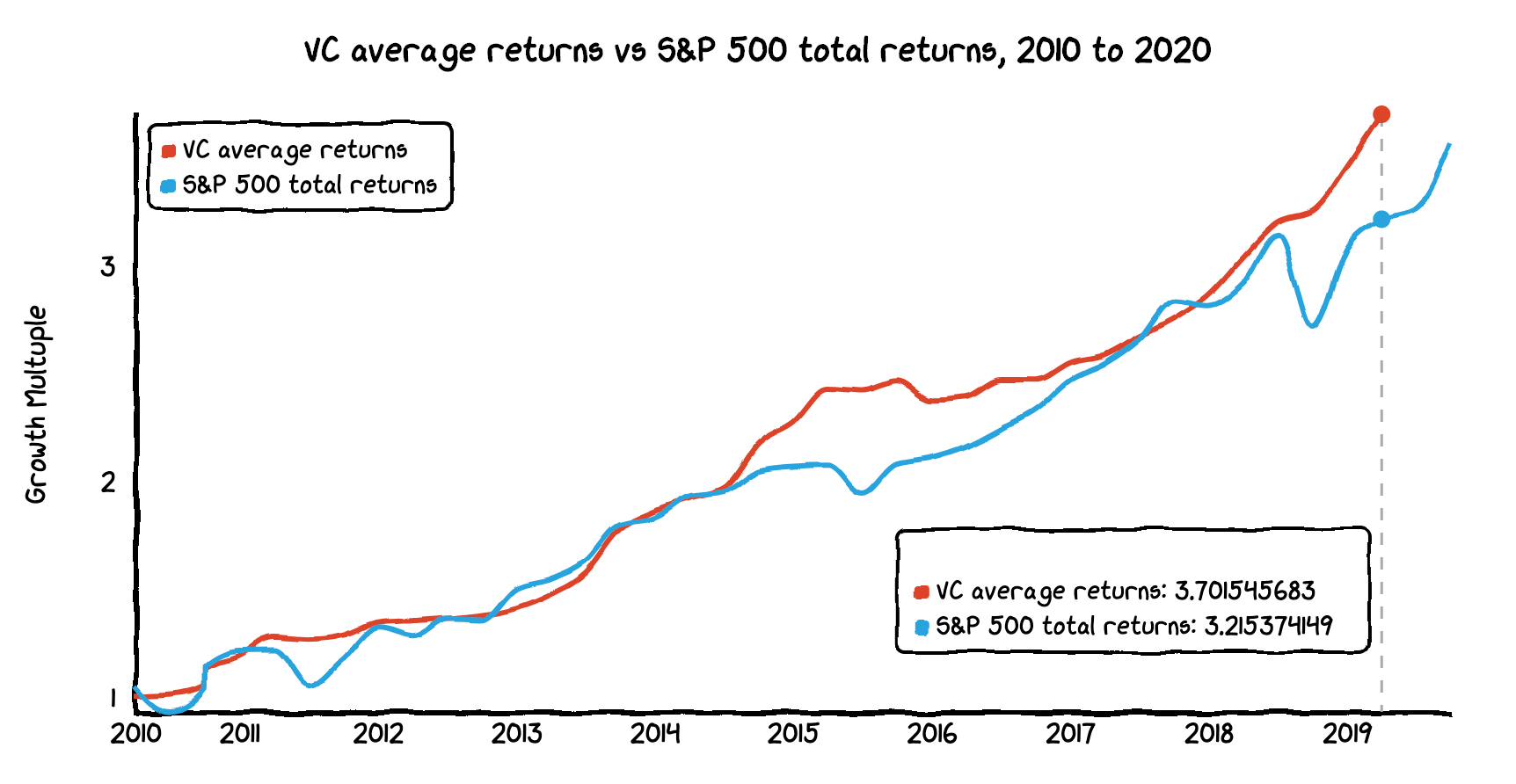

Anthony shows a graph showing Top VC, median VC, and S&P 500 returns. But, Top VC doesn't matter; that's like showing "top stock", which would be far ahead of the top VC fund. In fact, this shows that in the last 20 years, the median VC fund has vastly underperformed the S&P 500. Oh.

VC returns are difficult to compare because the asset class is so different than holding an ETF. Since VCs lock up money for 10 years or more, quarter to quarter returns are not as meaningful, because without a liquidity event, markups aren't even liquid. And just like with Private Equity, volatility appears to be lower due to the lack of liquidity.

Using his graph's source, Cambridge Associates's quarterly reports, in the almost decade recent period of 2010-2019 Q2, VC funds barely averaged to beat the S&P 500. And don't forget, for the privilege of these returns, there's no liquidity.

But, it's even worse. You can't invest in the average VC fund, because VCs have returns that follow the power law like startups (though, not quite as bad). Ahead of time, you have no idea how well a fund will do because it largely comes down to them investing in a breakout startup. In line with the AngelList early-stage data above, the median VC fund barely returns the fund, and only 15% return more than 2x.

So, to effectively invest in VC funds, you need a very long time horizon, invest in a wide number of fund vintages, have no liquidity needs, and are able to either get access to highly-effective funds (who hopefully can continue to do better than the median) or can invest in many VC funds. But, just as most startups don't want small checks, neither do VC firms. My accredited investor status doesn't mean Union Square Ventures would take my money, unfortunately. Who will? Unproven, micro-funds, which have incredibly high variance.

Principle: Outsized returns come from skill and labor

Even after adjusting for luck, there are indeed outsized returns available in private markets. Outsized returns most simply come from non-passivity: investors are either actively making skilled investment decisions, must manage hard assets effectively, or commit real labor.

For example, in many parts of the US, buying Real Estate and renting to tenants has returned favorably, especially using leverage and our favorable tax code. And while this includes investment skill—such as knowing the right markets to buy in—managing properties takes work. As such, outsized returns could still be expected, because the passive investor couldn't easily arbitrage it away.

The larger skill and labor component you incur, the more likely outsized returns are available. This means that we may expect that early stage venture deals—which have more due diligence, smaller check sizes, and are dependent on personal networks—may outperform. As we've discussed, however, due to variance, collecting these returns is difficult without sufficient capital.

Muddling the point

They quite literally prevent someone from doing something WITH THEIR OWN MONEY based on if they are a millionaire or not.

This is true, and is the strongest point. If the argument is just about whether the government has a right to keep people from making bad investments, he wouldn't have spent most of the article focused on VC and startup returns, though (see [1:2] again).

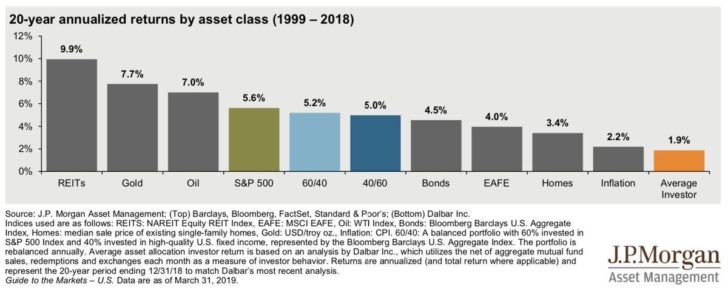

This chart is fascinating because it shows how the average investor underperforms everything. The average investor exhibits severe behavioral flaws in investing, and access to higher performing assets has not helped.

[P]rivate market investors are essentially dumping their bags on retail.

... the private market investor made many multiples on their money while the public market investor is only allowed to buy equity once majority of the value has been sucked out of the investment... Take a look at the early investors in every single one of these companies.

Comparing early investments that led to successful exits to post-IPO performance is disingenuous and misleading. It's a massive selection bias: these are the winners! Most other professional investors do not have exposure to any given successful startup. Further, those same successful investors took losses on the failed startups they invested in. So, again, he's pointing at how some people did well, yet implying the only thing preventing average people from exposure to these outlier returns are regulations.

This also ignores that there's a spectrum between early stage companies and those about to IPO. He's absolutely right that since companies are staying private longer, returns have been affected in public markets. Since he cites Uber, we should recognize that their share price had not meaningfully grown since late 2015 to their IPO, and the average dollar invested lost money. (Valuations grew, but after dilution, share price didn't appreciate.)

Mutual Funds, with fairly low fees, that invest in later-stage startups do exist and are large. This doesn't mean that all late-stage startup exposure is doing great. Just ask SoftBank.

It seems he's upset that upper-middle class investors have been locked out of the possibility to hit the lottery in startup investing. As we've covered, they nearly certainly wouldn't have had access (personal network, check size, etc), wouldn't have been able to appropriately diversify, and wouldn't have been interested in seed-level startup risk. However, in one day, during the February 2018 stock market flash crash, short-dated far out-of-the-money VIX calls returned better than Uber did during any year of its history. Of course, neither of us were holding those either. If what you want is high-variance and fat-tailed returns, at least it's available.

The problem with these three arguments are that (1) fraud is already illegal, (2) the new proposal is for people to get accreditation based on education and not wealth, and (3) there are no rules that prevent accredited investors from putting all their money in a single investment.

These points are true. Fraud is illegal, but that didn't stop a large portion of crypto ICOs from being scams. As I've mentioned, I agree that wealth is not education, so improvements to the regulation do make sense. This is where we may agree: a wider degree of risky asset classes should require further sophistication-based qualifications. Making rules based on wealth and income are overly simplistic. But, the vast majority of upper-middle class investors have not been discriminated against and proportionally very few would have realized massive outsized returns. Likewise, many unsophisticated rich people have very likely experienced poor returns from startups. Though, fortunately, not too many people are upset about that.

Wrapping up

Accredited Investor laws aren't effective. If anything, they poorly protect people from making bad investments in other vehicles and do not protect uninformed wealthier people. We could debate about whether the government should have this sort of oversight, but fortunately, based on real data from returns and practicalities of realizing those returns, the outcome has not kept the average investor from wealth in aggregate.

In fact, family offices—wealth owned and managed by incredibly wealthy people—represent a minority part of venture investments. The beneficiaries of VC returns include mutual, pension, retirement, and sovereign wealth funds, which do benefit average people [3].

So, we can agree that the laws may have been ineffective, but the data indicates that the largest thing they've done is reduced some forms of access—quite arbitrarily—to some high-variance assets that the average investor couldn't appropriately invest in. If that's the threat to the American dream, we'll be okay.

Further reading

I personally like investing in startups and other alternatives, which I realize is a privileged position due to current rules. I largely do it, however, for reasons outside of chasing higher returns, and stand to benefit from being involved in the startup ecosystem.

If you are interested in investing in startups, take time to understand risks, and what base rates are.

- Just Say NO To Angel Investing, It’s Not Worth The Risk

- Startup Growth and Venture Returns from AngelList (Important note: they only consider non-negative investments, so actual returns are much less. This show how the power law affects outcomes of successful exits.)

- Angel: How to Invest in Technology Startups by Jason Calacanis

- How to start angel investing by Julia DeWahl

Most definitely, the current laws are arbitrary. Assuming positive intent, they were likely an attempt to cover as much as possible, as simply as possible, yet fell short of the desired outcome. If Anthony's piece was titled "Accreditation Laws Ineffectively Protect Uninformed Rich People" or "Accreditation Laws Ineffectively Prevent People from Making Bad Investments", we'd have a lot more to agree on. But that'd be less clickbaity. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Covered later, most startups want to keep their cap table as simple as possible, so check sizes aren't typically tiny. This creates a perverse opportunity: those startups that are most open to small check sizes are also those with the least negotiating power. We've seen a similar affect on crowdfunding sites. One alternative, to deploy smaller amount of capital directly to startups, is through angel syndicates, which are a great way to learn about Angel investing. Think of these like micro-VC funds, complete with a customary 20% carry and SPV fees. ↩︎

CalPERS (California Public Employees' Retirement System) publishes their private equity / venture fund performance metrics, which are interesting. You can see the massive range of returns from these quite large funds. Compare to the data above from smaller funds, which have an even higher variance. ↩︎