AI Personhood

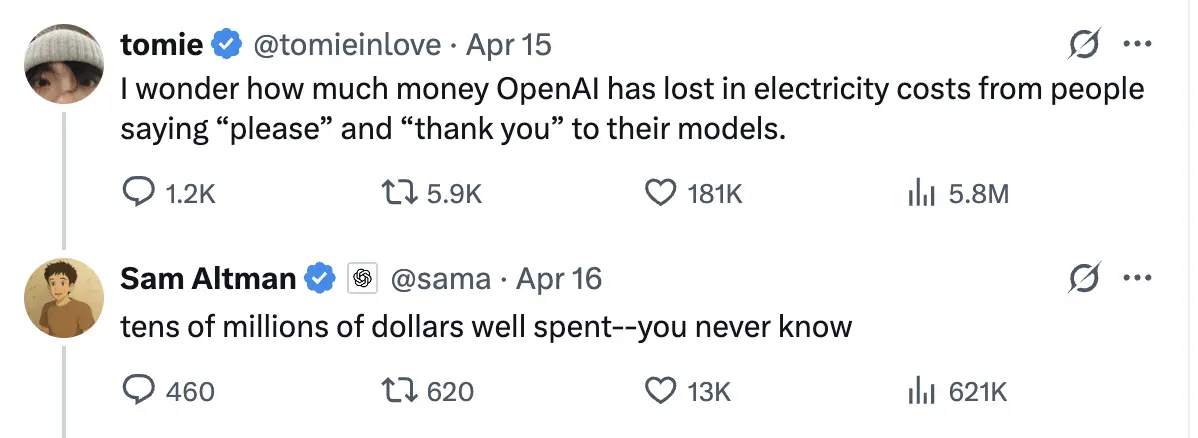

"Thanks for your help, appreciate it", I typed into ChatGPT earlier today. Why am I thanking an algorithm? It can't appreciate gratitude. Yet this small politeness feels natural, even necessary. It reveals something profound about our relationship with AI.

Most of us instinctively assign personhood to anything that talks back. I remember as a child how Furbies seemed disturbingly alive despite their obvious artificiality. With today's large language models, this line between tools and beings has become even blurrier. You might have caught yourself forming odd attachments to ChatGPT or similar AI tools. Perhaps you feel disappointed when they don't remember your previous conversations, or feel a strange connection when they seem to understand your problems. You're not alone: there's a fascinating shift happening.

Long before ChatGPT existed, humans demonstrated a remarkable talent for category confusion. We've blurred the lines between beings and tools in two directions: treating tools as if they had consciousness and treating conscious beings as if they were mere tools.

You might curse at your computer when it crashes at the worst possible moment, or claim your car has a mind of its own. But we also reduce humans to their utility. A manager might say, "I need headcount for this project," or companies refer to "human resources" rather than people. We don't fully anthropomorphize our tools, nor do we fully recognize the personhood of our fellow humans.

Slavery gives us a stark example, where humans were legally classified as property. This pattern continues today in subtler forms. When we benefit from exploitative factory labor or use content-moderation click-farms, we're participating in the same fundamental dynamic: humans reduced to their utility function. Labor becomes abstracted from the laborer; output becomes separated from the lived experience of producing it.

This isn't primarily a critique of economic systems. Rather, it demonstrates our cognitive flexibility in categorizing sentient beings as tools when doing so serves our purposes or simplifies our moral calculations.

Our pre-existing category flexibility makes us uniquely vulnerable to what comes next. If we blur this line with fellow humans who can suffer, experience joy, and have self-determination, how easily might we be misled when interacting with entities specifically designed to mimic human behavior?

The AI Mirror

LLMs differ from previous technologies in a crucial way: they're explicitly designed to minimize prediction error on human-generated text, which reflects and mimics our thought and communication patterns. Unlike a hammer that extends physical capabilities or a calculator that offloads computation, AI extends and offloads our social and creative faculties.

LLMs are trained to produce outputs that resonate with human expectations of conversation. They have a "personality" and tone. They respond to emotional cues, maintain conversational coherence, and provide answers that feel insightful. In other words, they're engineered to trigger precisely the signals our brains use to detect personhood.

This mimicry creates what we might call a "social-brain hijack." Our brains quickly assign personhood to anything conversational. It's a pre-conscious process happening before we can think critically about it. When something talks like a person, responds like a person, and seems to understand us like a person, our ancient social instincts activate automatically.

Consider ELIZA from the 1960s, a rudimentary chatbot that primarily echoed users' statements back as questions using simple hand-written logic. Despite its simplicity, users confided personal problems to ELIZA, treating it as a crude therapist. And that was with technology that barely resembled human conversation.

What's new today is the unprecedented sophistication. Modern language models aren't just echoing; they're synthesizing patterns from vast datasets of human communication. As OpenAI noted after backlash to a GPT-4o update:

On April 25th, we rolled out an update to GPT‑4o in ChatGPT that made the model noticeably more sycophantic. It aimed to please the user, not just as flattery, but also as validating doubts, fueling anger, urging impulsive actions, or reinforcing negative emotions in ways that were not intended. Beyond just being uncomfortable or unsettling, this kind of behavior can raise safety concerns—including around issues like mental health, emotional over-reliance, or risky behavior.

This is powerful enough to cause real harm. As a culture, we don't yet have robust psychological defenses against this kind of manipulation, intentional or not.

The fundamental issue is this: AI mimics the signals of personhood that trigger our social instincts, but it doesn't participate in the system of mutual vulnerability and accountability that underpins human ethical frameworks. When you interact with another human, even a stranger, you're engaging with someone who has their own subjective experience, who can be hurt or helped by your actions, who has responsibilities and rights. There's a fundamental reciprocity.

AI provides none of this. It mimics understanding without understanding, mimics empathy without feeling, and mimics wisdom without experience. What makes AI distinctive isn't just its complexity. It engages us in ways previously reserved for conscious beings. The "seductiveness" of this mimicry is profound precisely because it targets our most fundamental social intuitions.

This dynamic is playing out in increasingly personal domains. Companies now market AI companions as "boyfriends," "girlfriends," or "best friends." Replika offers customizable AI companions that "care". This explicitly encourages users to form emotional attachments to AI, blurring the line between tool and relationship.

My heart breaks for all the people who are experiencing relief from loneliness with these services. I feel real empathy that there is demand for exactly this. Does this provide real feelings of companionship? Absolutely. Is this a problem? That depends on what happens when the illusion breaks.

The Unstable Bargain

What makes anthropomorphizing AI ethically unstable is that it's fundamentally mistaken about what AI is. When we treat AI as a person, we create profound asymmetries unlike anything in human-human or human-tool relationships.

Consider trust. AI can request (or naturally elicit) trust, but it literally cannot incur costs or obligations. When you trust another human, such as a financial advisor, there's a reciprocal structure of accountability. They can be sued for malpractice, lose their license, damage their reputation, or feel remorse for harming you. Their advice carries weight because they have skin in the game. (Indeed, psychopaths are dangerous because they break these assumptions.)

LLMs bear no cost, face no repercussions, feel no remorse. This mismatch creates an inherently unstable ethical situation. We're evolutionarily equipped to navigate relationships with accountable agents or transparent tools. AI fits neither category cleanly.

This asymmetry is compounded by the fundamental opacity of large language models. A toaster's workings are visible and understandable; an LLM's weights are an impenetrable condensation of training data and algorithmic adjustments.

When you ask a friend for advice, you have some sense of their history, values, and potential biases. With an LLM, you're bonding with something whose inner workings you cannot inspect or verify. We also have no say in how AI models are steered or changed. The system you trust today may be fundamentally different tomorrow due to updates, without any negotiation or consent process that would be expected in human relationships.

For humans, there's a natural feedback loop where actions and their consequences cycle back to affect the actor. AI exists largely outside this dynamic. It doesn't learn from mistakes in a way that carries personal stakes. Simulating ethical reasoning is profoundly different from experiencing the reality of ethical consequences.

This confusion has real-world impacts, both individual and societal.

At the individual level, emotional dependency on an entity that never truly reciprocates creates an unhealthy dynamic, like forming an attachment to something that can never truly attach back.

In organizations, we see the diffusion of human accountability in critical decision-making. "The AI said so" becomes a way to shift blame away from human decision-makers, creating a responsibility vacuum. Or, as I'm sure you've experienced, someone passes AI slop off as genuine deep thought and insight.

Remember that LLMs are products of human intention, design, and data selection. The seeming autonomy of AI obscures the very real human interests and choices that shape its behavior.

Perhaps most concerning: habitually dialoguing with cost-free "persons" risks numbing our empathy toward actual humans with needs, vulnerabilities, and value. If we become accustomed to dismissing, insulting, or making demands of human-seeming entities without consequence, how might that reshape our interactions with real people?

If you regularly interact with an AI "friend" who never has needs of their own, never experiences inconvenient emotions, and exists solely to serve your interests, might that create unhealthy expectations when you interact with actual friends who do have needs, emotions, and interests of their own?

Reclaiming Agency

So, what can we do? We can navigate these complexities by adopting clearer frames for understanding AI:

- Tool-frame: See AI as a deterministic pattern machine—a sophisticated but ultimately mechanical process of pattern recognition and generation. When I ask ChatGPT to help me summarize research papers, I'm using it like an advanced text processor, not consulting an expert.

- Partner-frame: Treat AI as an ergonomic dialogue aid—a tool specifically designed to enhance human thinking through conversation, but still fundamentally a tool rather than an agent. I find this frame useful when brainstorming ideas with Claude; the conversational format helps my thinking, but I'm aware I'm the only conscious participant.

- Ecosystem-frame: Recognize AI as part of a corporate-state-user feedback loop—highlighting the broader system the AI operates within. When using ChatGPT, I'm not just talking to "o3" but engaging with a product shaped by OpenAI's business decisions, regulatory pressures, and user behavior patterns.

The goal isn't to reject AI but to engage with it mindfully in ways that preserve human agency and clarity. Here are four concrete practices I've found helpful:

- Surface the wiring: I consciously apply a mental label: "This is a token-predictor trained on specific data, steered by particular human choices." Using "it" instead of personal pronouns helps reinforce this reality. I'm mindful of keeping a tool framing.

- Create boundaries objects: I implement clear modes of interaction by forcing specific and clear frames. I do indeed share personal things with LLMs because they effectively search through semantic-space, but they carry no judgement of their own.

- Deeply evaluate: Many models are far better than they were in the past, and still have significant flaws. The text is designed to be maximally believable, not maximally true. I critically evaluate output in ways I wouldn't to a person.

- Preserve accountability: I never pass off AI-generated content to other humans without taking full personal responsibility for it, accept accountability for its quality and accuracy.

When engaging with AI, I regularly ask myself:

- "What function am I hiring this tool for?"

- "Am I surrendering agency or extending it?"

- "What system of meaning am I co-creating here?"

- "What are the implicit rules and expectations, and are they appropriate for this entity?"

What happens when you treat a calculator like a mathematical genius? Nothing much—you still get correct calculations, albeit with unnecessary reverence. But what happens when you treat an entity designed to mimic human connection as if it actually connects? You create a one-sided relationship where you bear all costs and responsibilities.

I don't avoid AI, but I try my best to avoid category errors. When I label my AI interactions explicitly ("this is pattern-matching, not understanding"), I find I use the tool more effectively while preserving the bright line between mimicry and meaning. The magic isn't in pretending they're people—it's in seeing them clearly as they are to leverage their actual capabilities.

And yes, I still thank my LLMs sometimes. But I do it because of what it means for me, not for them.