Investment returns

There's this funny dynamic of the past several years where people that act like investment returns come from thin air. It's weird, right? They talk about owning shares of some hot company, or exciting crypto project, but don't think about where the money (that they are sure to make) will come from.

What makes an investment worth more in the future? Simply: one where a future investor is willing to pay more than they are today. This entirely breaks many investment models, and highlights ponzi dynamics that are embedded in many investment decisions. This isn't doom and gloom, though: I'll show you how you can use this to make better investment decisions.

There's an obvious question: why would someone in the future be willing to pay more for an asset than today? There's many possible reasons:

- They don't have the information or knowledge that you have today. You may see the world more clearly than everyone else.

- You're being compensated for taking risk or inconvenience.

- Current investors can't access or saturate the market for structural reasons.

The truth for any asset is likely some combination of those. If you start a company, you start owning the whole company. If you build something of value, it's worth more because of all three reasons: you captured an open market opportunity that wasn't obvious to all, took on a lot of risk and had to actually start a company (not a walk in the park), and weren't willing to sell to investors.

I was an early investor in several private tech-related funds, like Calm Company Fund. I expected this fund to do well because I felt I saw the world more clearly than others: small, profitable tech companies were underserved by venture capital for structural reasons. I was willing to take risk on a new fund manager and asset class. Their funds have done well, but more importantly, my decision-making framework was good.

Investors aren't dumb, though. Freely traded markets can become efficient quite easily — most strategies are capacity limited because in open markets, opportunities shrink as people see them. Risk can be fairly well understood, even if only with wide error bars. There are frameworks to compensate investors for the risk they take on.

Most public market prices come from future projections. We see this with the Dot Com bubble and bust in the early 2000's:

Going into 2000, investors were exceedingly optimistic about tech companies, and believed future investors would be willing to pay more for tech company shares. This encouraged more people to see the possibility of tech, and also invest (projecting that future investors would pay more). This was a self-reinforcing cycle, and created a bubble. Eventually, it becomes more and more obvious that future investors won't be willing to pay these prices, and the prices quickly fall.

Equity prices like these don't have to come down. You just always need a consensus belief that someone in the future will pay more than the current price. When COVID hit, investors were less certain about what the future would look like. As regulatory bodies made their intentions clear and more was known, markets rallied. On a small scale, something can look like a bubble—such as a startup's fast rising valuation—but actually just be reflecting updated estimates about future investor appetite.

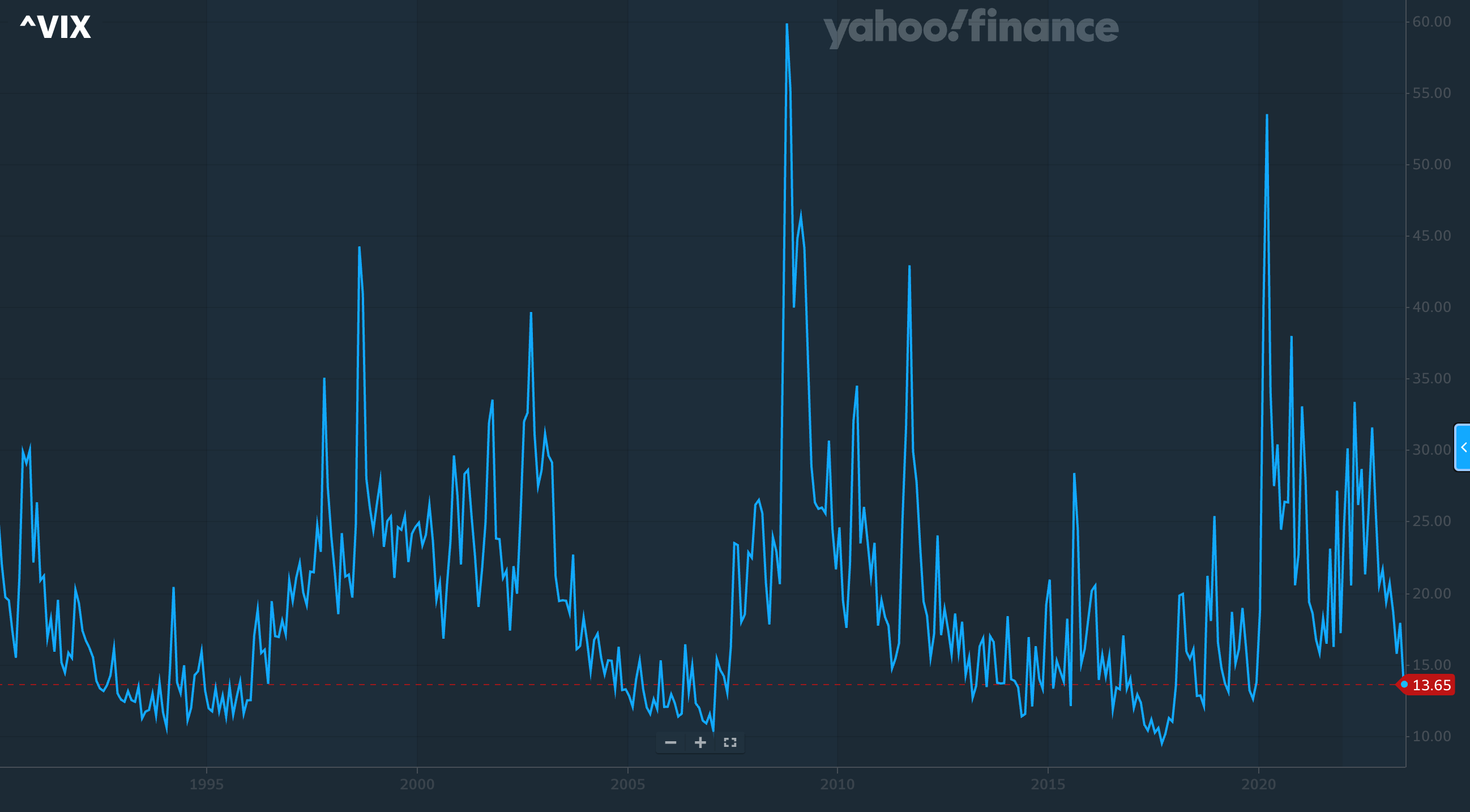

Some assets typically behave differently, and mean revert over time. For example, here is a long term chart for the VIX index, which is an index that measures expected future volatility of the S&P 500:

At the highest extremes, markets have a lot of fear, and people willing to take risk are compensated highly. At the lowest extremes, markets feel comfortable and safe, and people taking risk are not compensated nearly as much. This oscillates based on sentiment and other macro-economic factors, but seems to find equilibriums on a larger timescale.

The same goes for many commodities. Wheat and corn can have shortages and surpluses due to weather and other macroeconomic effects. Overall, though, it'll be grown so that producers are slightly profitable after all expenses, so we can expect prices to overall be pulled towards some longer term average.

There are no asset classes that over-perform on a risk-adjusted basis forever. All exponential systems terminate, eventually. Certain asset classes can look great on paper—such as search funds—but require a lot of labor to extract: no one has figured out how to deploy a few billion into search funds. Returns have to come from somewhere, and that somewhere is typically fairly rational.

With this framework, we can look at several asset classes to see where returns come from.

Cryptocurrencies are worth exactly what other people in the market are willing to buy them for. The fundamental thesis is basically "price goes up because more people will want it", so we regularly see very large price swings as people's emotions, expectations, and appetites oscillate. Calling crypto a ponzi is sort of true, but in an unhelpful way. It's true to the extent that other assets without full intrinsic value are ponzis, like gold. There may be utility in them, but that's besides the point. They gain in value because people will pay more in the future. This is neither good not bad, it just is.

The crypto True Believers that I know believe they see the world more clearly than everyone else. And, as it turned out, crypto ended up being particularly memetic: over the past decade, more and more people did want to buy crypto. The delay between "my informed technorati circle of friends know about crypto" and "my barber knows about crypto" ended up being cultural and informational. It's not anything about blockchains that make it valuable; it's that future people will want it. Worthless crypto tokens may have the same blockchain guarantees as Bitcoin, but no one wants them.

Open markets tend to be priced pretty well, because inefficiencies can be closed fairly quickly. Every person buying an underpriced asset raises the price, and vice versa for selling. I have no idea what will happen with crypto in the future or if it'll become more useful, but I do think that any strong crypto thesis requires confidence in projecting future excitement and appetite better than others.

In certain circles, everything from the stock market to residential real estate to the US dollar are accused of being ponzi schemes. This has a weird element of truth. Why has residential real estate performed so well over the past couple decades? People are willing to pay more. Why? Risk has been subsidized with Fed-backed mortgages, rates have been unusually low leading to cheap leverage, and there has been a general mismatch between market supply and demand. These are all good reasons that lead people to pay more and more for the same asset, but the price going up was entirely reliant on this.

Can this continue? For a while, perhaps. Regulators keep finding ways of propping up prices, transferring more and more wealth to existing asset holders. (This is messed up, right?) But, forever? No way. On a long horizon, real estate can't outpace wages, since eventually people simply cannot buy what's being offered. The more risk and prices are subsidized, the longer it can go. Eventually, it breaks.

The same dynamic occurs in the stock market. In The Rise of Carry, the authors make a case that central banks suppress volatility systematically, encouraging high leverage risk-taking behavior. The world seems less risky than it actually is.

Long term, this leads to three critical outcomes. First, it makes prospering in financial markets less about competence and more about insider status, as insiders with weak balance sheets are able to survive carry crashes thanks to central bank action. Second, it reinforces wealth inequality by truncating losses for already wealthy investors who do not necessarily need, but nevertheless benefit from, action to suppress volatility. Last, the distinction between economic recessions and financial market downturns becomes increasingly blurry. Recessions no longer cause severe asset price declines, or bear markets; they are a function of the asset price declines.

— The Rise of Carry

They published in 2019, which was right ahead of one of the massive Fed spending spree to stabilize markets in the wake of the pandemic. Volatility suppression, risk-taking, and leverage are not necessarily bad. However, they encourage markets to become disconnected with economic reality. Every crisis that is saved by policies that double-down on this dynamic make the problem worse. Who loses when residential real estate gets propped up? People who already struggle to pay for housing.

10 years ago, I read The Single Greatest Predictor of Future Stock Market Returns. It shaped how I thought about asset allocation:

Many investors don’t like the fact that price drives total return. If price drives total return, it follows that total return is a function of the shifting sentiment, preferences and expectations of other people–those who make up the market and “vote” on what the price will be. Investors don’t want their returns to be subject to the arbitrary “vote” of other people, and so they pretend that as stock market speculators they are actually genuine businessmen who “buy” and “own” companies to hold forever. They tell themselves that their returns will somehow emerge directly from the cash flows of the underlying businesses, regardless of what the market decides to do with price.

...

To claim a return on a stock in any other context, an investor needs someone to sell it to. The price that other people are wiling to pay is therefore important–supremely important. Rather than resist this fact puristically, our responsibility as investors is to accept it and work within it, by understanding the behavioral propensities of our fellow market participants, and getting in front of emerging trends in how they choose to allocate their wealth.

...

Ultimately, valuation is a learned perception, learned through a process of social and environmental reinforcement... Stock prices don’t change because market participants choose to assign stocks different P/E multiples. Rather, they change because the eagerness of the aggregate investment community to allocate wealth into stocks rises or falls.

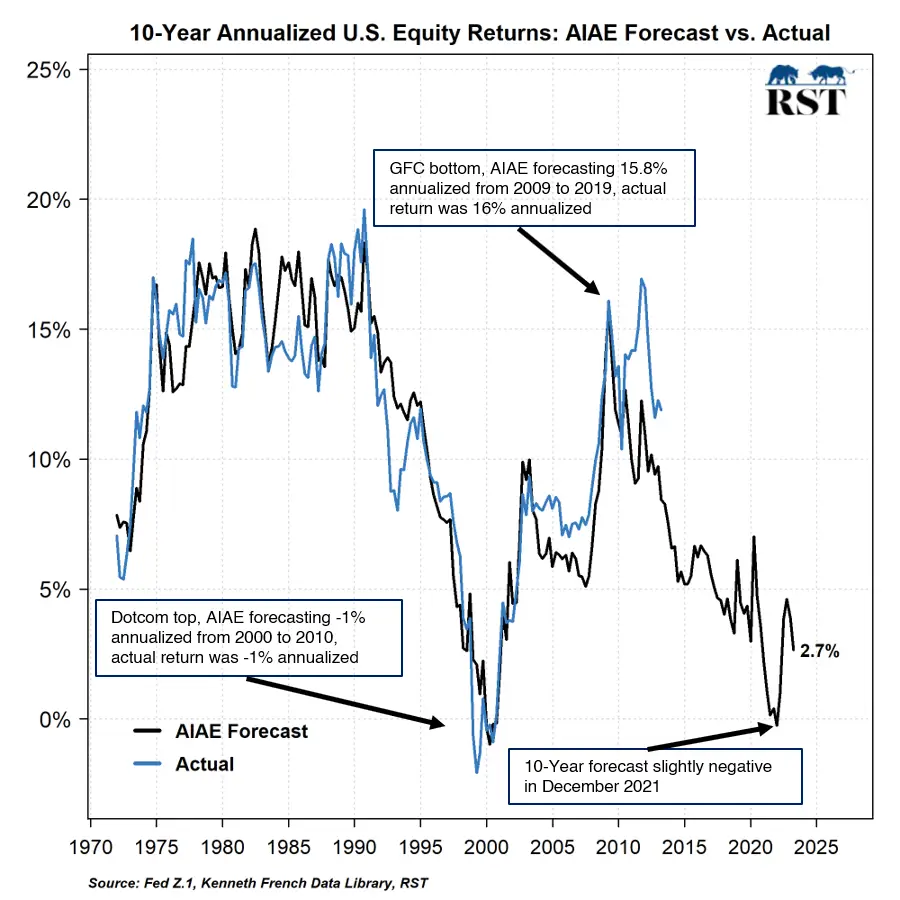

The author constructs an indicator that predicts 10 year returns of US equities, which shows times that have likely high future returns and times that have likely low future returns. Recently, PortfolioOptimization looked at how it has performed over the past 10 years. Here's an updated version of the model:

There's a lot of subtleties, and actually making investment decisions based on this model isn't actually straightforward. It's a model (i.e., can be wrong!) that predicts 10 year average returns, but doesn't tell you what to do today. Raymond Micaletti published an allocation model in 2020 that shows the indicator can be quite helpful, though. Allocate Smartly also built a model, showing that it does improve returns and reduce volatility, but that the indicator can also be misleading for extended periods of time.

If this model holds, we're looking at disappointing equity returns over the next 10 years. Let that sink in: it's likely that the recent amazing performance of US equities "pulled" from the future, and returns over the next several years may be tepid. This does not mean to sell everything — I have plenty of US equities exposure. But it does mean that simply parking money in passive investments and hoping prices will keep rising may be foolhardy.

What we need is diversification. In the next essay I dive deeply into that, but for now, we'll focus on wanting to find differentiated returns: assets with positive expectancy that are unrelated (or at least, unrelated-ish) to the rest of the US stock market.

If you want to invest in unusual, different things, you can find exactly that. Markets like to give people what they want.

You've probably seen ads for Masterworks, a platform that allows people to buy shares of "blue chip" art. The idea is that art is uncorrelated to the stock market, and has done quite well historically, so the asset class should be available to regular people like you and me.

This trend is growing quickly. Other platforms doing similar things include Yieldstreet and Rally, and there's several platforms to buy shares of private startups, such as Wefunder and Republic. The pitch is more emotional than anything: wouldn't you want to make money with the sorts of private investments that rich people have access to? The nice thing is that it's near impossible to even know what the average performance of the asset class is, so these companies can point to unusual outcomes as examples of what could happen.

This is just as disingenuous as lotteries showing the jackpot size and making cute ads with old people who won, showing their RVs and smiling grandchildren. The same logic draws people to want to invest in startups, because many startups have returned over 100x the initial investment. I looked at the venture capital asset class several years ago, before the huge COVID / zero interest rate rise in startup valuations. Since then, on paper, startups (as an asset class) did far better than private markets and then valuations collapsed. Many companies that looked amazing on paper have already gone through layoffs and are trying to survive. This is an expected cycle.

To beat a dead horse: investment returns come from the willingness for future investors to pay more for your assets. When people are less optimistic about free money from the Fed and future prospects, valuations drop quickly.

This isn't to say that investing in many asset classes is bad. In fact, diversification of poorly returning assets can paradoxically improve a portfolio's risk-adjusted return, since non-correlated assets will have good and bad periods at different times, statistically. However, let's think about these asset classes and where future returns might come from.

Fine art, as an asset class, has done well historically. Obviously, this could just be a sample bias: we're not talking about asset classes that haven't done well (Beanie Babies, anyone?). And frankly, our historical sample is dominated by specific art pieces that increased in price (pieces that fall in price don't sell!). So, it may not be that buying a random "fine art" piece should have any expectation of increasing in value. For those pieces which did increase in value, we need to remember our rule: it's done well because people pay more now than they used to. Art offers status to rich people, and people want status. For art to continue to do well, future buyers need to be willing to pay more than they will today.

As owning shares of art becomes easier and easier, do you think owning art will confer the same status? Should we expect the cultural trend of rich people valuing art higher and higher to continue? That's a pretty specific bet about future status markets, so I can't answer for certain, but am doubtful. If an asset has done well due to access, as everyone gets access, future returns are usually tepid.

Many markets have ponzi dynamics to some extent: they rely on future people paying more for assets, so structural incentives revolve around attracting new capital. This is mostly unavoidable: nearly all assets have this dynamic. Minimally, when we make active asset allocation decisions, we should have an idea why it's plausible that we're seeing the world more clearly, taking on risk or inconvenience, or have special private access.

Each of these has clear failure modes. Being confident about seeing the world clearly doesn't mean we're right, and appearing to be right doesn't mean we saw the world more clearly. In life, we have a tiny sample size. Deciding to buy and hold Amazon once in the late 90s would have outperformed nearly every other asset class and investment manager. It's easy to be right and the outcome still disappoints, or be wrong and get lucky.

Risk is a messy demon. It's rare that we ever know exactly what risks we're taking. Very smart people have blown up funds by misunderstanding risk. Risks are easy to hide, especially if the downside has never happened yet. Inconvenience is far easier to understand. Being a landlord may give higher risk adjusted returns because it takes actual labor. Likewise, running a boring profitable local business is hard. Passive investing is so much easier.

Private special access is indeed possible, but also is a breeding ground for greed and fraud. Many get-rich-quick schemes have an element of "let me let you into this exclusive club". It's nearly impossible for normal people to get access to many well-run large funds which would provide differentiated returns.

Where does this leave us? Returns come from somewhere. Not all investing is for impact, but we all invest for a reason. For you, part of this may be ethical: finding investments where your money helps bring something new into existence. Or it may be to plan a comfortable future for your family. For me, I want leverage in the world.

Learning to understand where returns come from gives a very real edge. You know what you're looking for, and what needs to happen to be paid. You understand the motivations of the future people who will value your assets higher. You're able to avoid empty hype cycles, while also taking deliberate risks when they're aligned with the future you envision.

As the NFT bubble taught many people, while it's difficult to significantly outperform markets, it's also easy to underperform.