Prizes

True progress doesn't come from incrementalism, detailed plans, or good intentions. It comes from actually solving hard, seemingly intractable, nebulous, sticky real-world problems. Greatness cannot be planned, after all. Yet, so much of our current system for advancing science and technology relies on all the wrong incentives — monopolistic market capture through IP ownership and incrementalism science through peer-review and grant processes.

What if we took a radically different approach? What if, instead of relying on private market incentives to align with greater good, or doling out grant money for incremental projects, we opened up the process and offered sizable rewards to anyone who could solve a specific, difficult challenge?

This isn't a new idea. Nearly 300 years ago, the British government passed the Longitude Act in 1714, offering a prize of around $2 million in today's money, to the person who could devise a practical method for determining a ship's longitude at sea. It took decades, but clockmaker John Harrison finally found a solution, and in the process, revolutionized ocean navigation and saved countless lives.

Solutions often come from outsiders. The key elements of this approach are:

- Identify an important problem

- Attach a meaningful monetary reward to solving it

- Open up the challenge to everyone

- Rigorously test and validate the solutions

A historical example of this is the progression of long distance flight before there was a commercial aviation industry. The Daily Mail offered a series of prizes, starting in 1906, to incentize teams to accomplish longer and longer flights. At the time, the best pilots could only fly for a few seconds. In 1910, Louis Paulhan won the first prize for a 195 mile flight between London and Manchester. By 1919, French hotelier Raymond Orteig offered $25,000 to the first aviator who could fly nonstop from New York to Paris — also regarded as impossible. In 1927, an unknown 25-year-old airmail pilot named Charles Lindbergh won the prize (and worldwide fame) by completing the trip in 33.5 hours. The achievement shocked the world and ushered in a new age of aviation. Single accomplishments can unlock progress in entire industries.

More recently, the $10 million Ansari X Prize in 2004 kickstarted the private spaceflight industry by challenging teams to build and launch a reusable manned spacecraft — a feat that seemed like science fiction at the time. And from 2004 to 2005, the DARPA Grand Challenge offered a total of $3 million in prizes for autonomous vehicles that could navigate a course in the Mojave Desert. The first year, no car got further than 11 miles. The next year, five vehicles completed the entire 132 mile route. Less than two decades later, most modern cars have elements of self-driving technology. Innovation happens astonishingly fast when the right incentives are applied.

Why don't we do more of this? Governments and large corporations are prisoner to bureaucratic inertia. In private markets, we reward monopoly ownership of ideas in a way that prevents the best innovations to become ubiquitous. Imagine if a single company owned the Internet. We're lucky that we have many open technologies, but this doesn't necessarily happen by default when there are very large corporate interests. Google killed RSS (by killing Google Reader) because they had other strategic objectives. Likewise, governments invest billions into science research, but it is far easier and safer to fund what has always been funded than to embrace the uncertainty of a wide-open innovation marketplace.

Science bounties work best for applied technologies and tangible inventions — things that can be definitively achieved and empirically validated as either working or not. Much of scientific research, especially basic research, is fuzzier. How would you structure a prize for expanding humanity's understanding of fluid dynamics? Or for discovering the neural basis of consciousness? Thus, bounties don't entirely replace grants and existing incentives.

Instead, there are many scientific and technological challenges that are perfectly suited for the prize model. Off the top of my head:

- Scalable carbon removal technologies to help reverse climate change

- Next-generation power generation and distribution

- A universal flu vaccine effective against all strains

- Cheap, efficient batteries with 10x the energy density of today's best chemistry

- Novel antibiotics to counter the looming superbug crisis

- AI systems that can diagnose disease more accurately than human physicians

- Methods for cleaning up plastic and other pollution

- Algorithms that can predict the efficacy and safety of new pharmaceutical drugs

- Creation of a real room-temperature superconductor

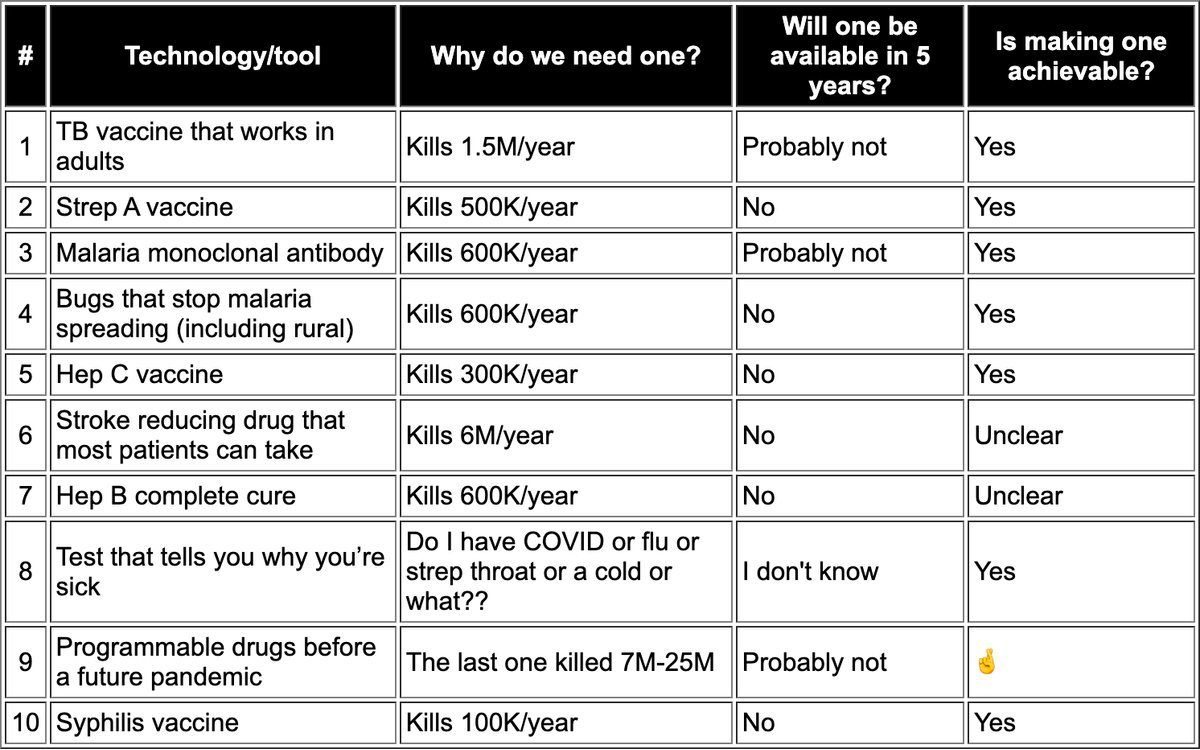

And I'm certain there's many more great fits. This table made the Twitter rounds recently:

The potential breakthroughs are endless, and the good they could do for the world is incalculable. To get there, we need to be willing to rethink some fundamental assumptions about how science gets done, and who benefits from major advancements.

The key is finding problems that are very hard—seemingly intractable—with unclear paths towards incremental progress. The result should be a dividend to all, not locked down by extractive IP ownership. Yet, monetary incentives can't be avoided.

First, we need a shift away from the publish-or-perish mentality in academia, which incentivizes incremental, esoteric research over high-impact, practical work. Science is a strong-link problem, so having more wild ideas is a good thing. We need to bust up existing incentives and invite real competition. Finally, we need to expand our conception of who can participate in science in the first place. Some of history's greatest inventors were self-taught amateurs. Solutions to big problems can come from anywhere.

We should do everything possible to maximize the number of people working on hard problems. There will be failure — this is a feature, not a bug. Yet, when we have big successes, advancements in knowledge should flow to everyone. No one owns the periodic table. No one has a monopoly on the laws of physics. Scientific knowledge is the common heritage of humanity.

Private companies excel at innovating when there's a clear market opportunity and the problem is well-defined. But some of the biggest challenges we face as a society—from combating climate change to curing cancer—are too intractable and risky for businesses to tackle alone. This leaves a perfect hole for governments and large philanthropies. These institutions have the scale, the time horizon, and the ability to invest in long-term, high-risk, high-reward innovation for the common good.

The early space race, Human Genome Project, and the early internet wouldn't have happened just relying on private companies solving for known, existing markets. The key is to pair the resources and long-term vision of the public sector with the dynamism and ingenuity of the private sector. Create a thriving ecosystem of innovation where government bounties and prizes spur breakthroughs that entrepreneurs then scale up into competitive, mature industries.

It's up to us to demand this of our politicians (and friendly billionaires 👋).