Supplements

I'm a bit of an interventionist: I enjoy tweaking systems, experimenting, n=1, and so on. And along that comes a lot of research. This time, I'll save you a lot of time and risk so you understand more about supplement science and how the industry works.

The supplement industry is wild. Through a historical quirk it's largely unregulated in the US. I'll save you the history lesson, but it involves an industry propaganda TV ad where Mel Gibson gets arrested by the FBI for taking vitamins. Scary stuff. But seriously, watch the ad:

Getting a good outcome—the right compound being taken by the right person to help with their goals—is largely determined by chance and access to reliable information and wise (lucky?) decision making. As in, it's a crapshoot. Most supplements in grocery stores are garbage, because the ingredients don't do much, are dosed incorrectly, or are of the wrong chemical forms. Alas.

Yet, I take several supplements regularly, and have experimented with many more. There's a few reasons someone may take supplements or other compounds:

- Filling gaps in your nutrition. This is okay. It's better to fill gaps with real foods, but this isn't always possible or practical.

- Longevity and wellness. Everything from NAC to NMN is promised to make us live longer and healthier. Health claims are often vague and open-ended.

- Fixing something acutely. This might include poor sleep, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, etc.

- Achieving an acute effect. Some things have an obvious effect, such as improving concentration and increasing exercise endurance.

Each of these usually overlap for any given supplement, so someone may take something for some small acute effects and longevity. Some motivations may be more direct, such as how vegans and vegetarians often have clear gaps in their diets that they may want to fill.

Supplement research

Doing your own supplement research is hard. In fact, supplement research in general is a hard problem. We'll ignore people who take supplements based on TV ads, hearing about some new plant extract from friends, etc, and assume that you carefully consider evidence to decide what to supplement.

I'm a fairly competent researcher, and worked closely to the supplement and wellness industry. Here's the dirty secret about supplement research: what passes as "science" is fairly low, many studies are poorly designed and underpowered, and industry incentives make most results pretty murky. What people want is "how will this supplement work for me and my unique body, situation, and goals?". What's available is... not that.

Let's take a look how this works in practice. Picked arbitrarily, collagen is often recommended by health influencers to improve exercise recovery, joint health, etc. There are hundreds of brands selling collagen of different forms online, and there's many types of collagen. This is not a niche supplement, you probably know several people who supplement with collagen.

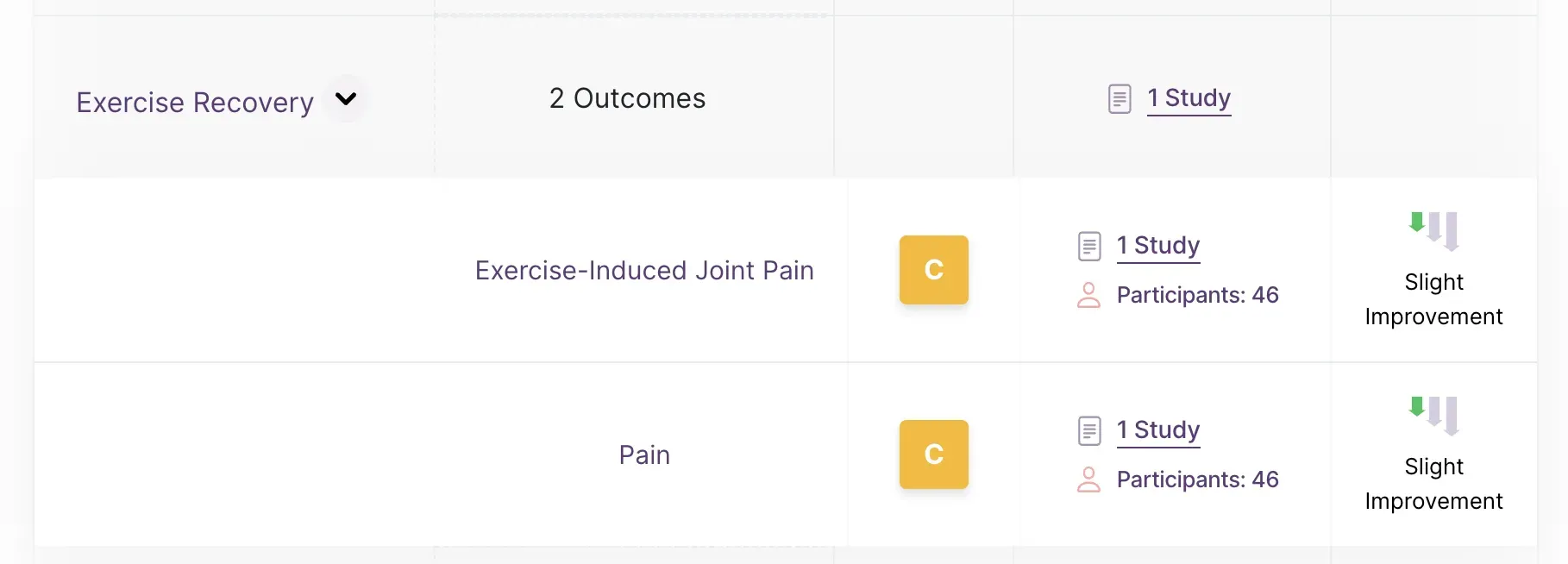

Examine is one of the best place for high-quality supplement research. Here's what they have for collagen and "Exercise Recovery" (which is actually the same outcomes as for "Joint Health", I'm not cherry picking I promise):

The "1 Study" each are actually the same study. So all the evidence Examine has for exercise recovery and joint health comes from a single C-rated study. Why is this single study rated a C ("Low potential")?

Funded by a supplement manufacturer, they studied 24 (the other half were on placebos) overweight people with an average age of 46, and found some improvements to knee extension. The treatment arm improved on average 6°. We don't see if this was a few people increasing a lot or everyone increasing slightly. Either way, to not miss the forest in the trees, this is a mobility limited group to begin with! The average starting knee extension was 74°. I don't know what's normal, but mine is quite a bit higher. Additionally, no improvement was found for knee flexion (bending in the other direction).

But we're here for exercise recovery and pain. The study looked at several metrics of improvement, and Examine shows slight improvement to pain. Let's look at what they actually found. First, quite a bit of nothing:

- "... there was no overall reduction in joint pain as assessed by KOOS" (a subjective rating test for pain)

- "No significant differences were observed between the study groups for the six-minute time walk or the daily number of steps taken"

- "Both groups began to recover from pain with the same rate resulting in no significant differences between groups in the time to initial offset of joint pain"

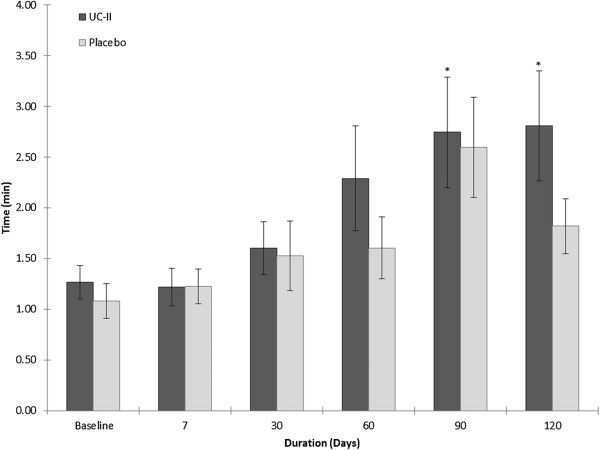

This leaves us with the one pain finding they found: onset time to joint pain during exercise.

There's 12 measurements here (two for each duration), and they call out that the 90 and 120 day treatment group improved vs the baseline. Yet, notice how large the error bars are and how the placebo arm also statistically significantly improved on day 90.

Taking an outside view, we're supposed to believe that the placebo arm experienced statistically significant improvements between day 60 and 90, and then regressed on day 120. Skeptically, there's no reason we should expect to see that in the placebo arm. The best way to interpret this is that joint pain may just get better over time by itself, and the data is entirely inconclusive as to whether collagen did much. (Remember, participant pain was measured in other ways, and nothing was found.)

In total, this study used a population that may not resemble you (age, overweight, mobility impaired with knee pain), made multiple dozens of total measurements, found small improvements in knee extension but not knee flexion, may or may not have found very slight pain improvements, and found quite a few no improvements on metrics they measured.

More clearly, they show slight evidence that "for a specific group of mobility impaired, overweight people with knee pain around 45 years old, collagen supplementation for many months continually seems to slightly improve knee extension". You may actually want to answer "for me, will collagen help my overall joint health?"

This, in total, is the study evidence we have on Examine. That's it. So, should we take collagen for "joint health"? I don't think anyone can answer confidently.

We can do this with any supplement. The bar for research is low, the studies are mediocre in general, and industry incentives pollute the signal. This doesn't mean nothing works, but that you can't just hear that a study shows X, and actually believe that applies to you.

I encourage you to do this exercise for other supplements that you're interested in. For many supplements, it's even trickier. For example, Omega 3 fish oil—incredibly popular and fairly expensive supplements—shows strong evidence to lower blood triglycerides. Evidence for many other outcomes is far weaker and mixed, yet Omega 3's are commonly taken for general "cardiovascular health". But, lowering triglycerides should be good and reduce adverse cardiovascular events, right? Perhaps, and perhaps not:

Meta‐analysis and sensitivity analyses suggested little or no effect of increasing LCn3 on all‐cause mortality (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.03, 92,653 participants; 8189 deaths in 39 trials, high‐quality evidence), cardiovascular mortality (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.03, 67,772 participants; 4544 CVD deaths in 25 RCTs), cardiovascular events (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.04, 90,378 participants; 14,737 people experienced events in 38 trials, high‐quality evidence), coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.09, 73,491 participants; 1596 CHD deaths in 21 RCTs), stroke (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.16, 89,358 participants; 1822 strokes in 28 trials) or arrhythmia (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.05, 53,796 participants; 3788 people experienced arrhythmia in 28 RCTs).

— Omega‐3 fatty acids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease

This is further complicated by there's multiple types of Omega 3s (ALA, EPA, DHA), oxidation is a rampant problem in most Omega 3 supplements, heavy-metal levels are quite high in many Omega 3 supplements, and supplement dosages are often much lower than studied dosages. As in, even if there was an effect, there's a good chance the average person wouldn't see it because of poor supplement quality.

Again, scientific studies look at one very specific thing, and you likely care about something far more specific (applying to you) and general (applying to your overall health, not only one marker).

This doesn't even yet consider that supplements interact with very complex systems, and may achieve certain impacts at the cost of other things that actually matter. Let's pretend that Omega 3s would indeed reduce your blood triglycerides and that leads to lower risks of heart attacks, but that it accomplishes this at the risk of increasing stroke risk. You'd be trading one risk for another, in a way that's quite difficult to control for. In this world, deciding whether to take something becomes so much more complicated — have a (slight?) benefit vs possibly unknown risks.

Seems far fetched? Not at all. Niacin reliably increases HDL cholesterol and lowers LDL cholesterol (good directions for both), but at the cost of likely increasing insulin resistance. Thus, we can potentially trade off adverse cardiovascular events for Type 2 diabetes. So when you consider taking niacin, you don't only care about "will niacin improve my cholesterol?" but also "will niacin adversely impact my health in other ways?"

This is one of the core problems with supplements that have shown reliable effects: they do more than one thing, and you may want one of the effects, but not the others.

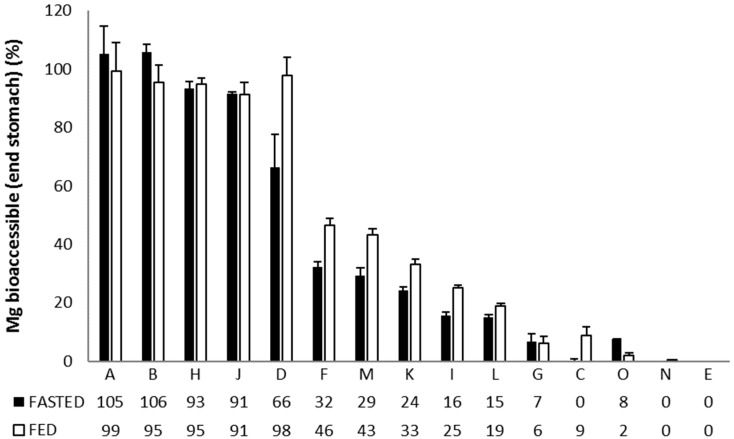

It gets worse: when you buy supplements, you're often not getting what you think you are. Plenty of compounds are not bioavailable — there's no mechanism to deliver the supplement to the right place. Most people are deficient in magnesium, and there's good research supporting supplementation. But we can't absorb elemental magnesium by itself. When you supplement, you assume the compound actually gets to where it needs to go, but this isn't always the case. Here's a study that looked at magnesium bioavailability of 15 different supplement formulations/brands:

Some absorbed well, others barely at all. I spot checked reviews online of several of the poorly absorbed brands, and they seemed fine — many people like them! In fact, a couple of these brands are available in local stores near me, likely implying people buy them and think they're "working".

Scott Alexander wrote about this specific problem:

Magnesium is a metal. There is no complicated extraction process. There’s no debate over which ingredient is the active one. It’s just magnesium. You either have it or you don’t. Some suppliers bind it to different molecules, and others do special things to make it bioavailable, but something that claims to have 100 mg magnesium should always have 100 mg magnesium.

Labdoor analyzes 30 brands of magnesium supplement. 25 earn As, 3 earn Cs, and 2 flunk. Of the two that flunk, one has only 60% as much magnesium as claimed, and the other has almost 3x as much magnesium as claimed. No product has an unsafe amount of heavy metals, although the worst have between a third and half of the government’s safety limit.

ConsumerLab analyzes twelve magnesium brands. Eleven pass and one fail. The failure had only about 80% as much magnesium as claimed. The brand that Labdoor said had 3x the claimed amount of magnesium was completely fine according to ConsumerLab, although Labdoor checked the neutral flavor and ConsumerLab checked the raspberry flavor. The company involved claims to have done an investigation and found that their supplement had the amount they claimed, so it’s possible Labdoor was in error here.

And magnesium is easy! Once you look at plant extracts that are not standardized, it gets even murkier. From Scott's post again, quoting the owner of Nootropics Depot (a supplement vendor that I personally trust):

If you knew the half of the shit that goes on in the background of this industry, you'd be disgusted. My lab director went to the AOAC conference last week. Scientists from most of the analytical labs in the US were there, and many of the quality directors from the bigger brands. My lab director was just openly calling products out that we tested and had failed, and everyone was looking at him like he was breaking decorum. There is an unspoken rule in this industry that you don't call out other brands for quality issues, because you know you have some of your own. It's insane! Everyone knows all the products fail. Everyone knows almost nobody is doing things right. However, the status quo makes too many people too much money to change.

Pretend a researcher wanted to retrospectively look at long term magnesium supplementation to look for health outcomes by surveying people. They start out with tons of confounders, because people who buy supplements are different than people who don't. Then, they're relying on people's memory, going back several years. Someone who reports as a regular magnesium supplementer may have skipped a couple years without remembering. And then, we don't even know if they were taking reasonable doses (perhaps far too low) of actually bioavailable forms. Overall, this study is probably impossible to do right and get meaningful results.

I'm not being critical of collogen, Omega 3s, and magnesium. I've taken all of these. Instead, I'm showing how difficult of a problem this actually is, and how much skepticism you need to carry.

Wellness and longevity

Let's revisit why someone may take supplements. The first reason I listed was to fill in nutritional gaps. You'd take non-super-physiological doses of food-like substances to fill in gaps that you know you have. For example, vegans and vegetarians may want to take L-carnitine, Creatine, Omega-3 fatty acids, and Vitamin B12 because they know their diets are deficient. (Another plug for Examine's supplement guides, which are quite good.) This is why green powders, like AG1, are popular: people think of them as nutritional insurance for gaps in their diets.

While getting nutrients from whole foods is preferable, with good research and careful sourcing, filling nutritional gaps this way is reasonable. For example, I supplement with magnesium glycinate and creatine because the evidence is solid for outcomes I care about, and I likely consume less than optimal amounts through my diet. Both of these are well studied, low risk, have clear benefits, and are fairly cheap. The goal here is taking physiologically-sized doses of compounds that are readily available in diets theoretically, but yours doesn't have enough for whatever reason.

The next reasons to take supplements, longevity and overall wellness, are the most messy. These outcomes don't have great markers for studies to look at, and studying them takes many years. I'm intensely skeptical of any supplement that lacks a clear understood causal mechanism for why it'd help improve longevity and overall "wellness".

Nicotinamide Riboside (NR), Nicotinamide Mononucleotide (NMN), and similar compounds—they're all targeting the same thing—are popular compounds people take for longevity, with many health influencers touting their benefits. And, not surprisingly, plenty of skeptics as well. This points at one fundamental issue with supplement education: everyone is selling something, even if the thing their selling is their own personal brand.

Again, this isn't to say that nothing is good to promote longevity. However, I'm fairly confident that for most people, most dietary and longevity supplements will have a lower impact than improving their diet and increasing exercise. Those come so far ahead, yet many supplement enthusiasts lose the forest in the trees.

Acute effects

Next, many people take supplements to fix something acutely or achieve a specific effect. Another dirty supplement secret: many supplements taken for a specific effect are just worse versions of pharmaceutical drugs. From an outside view, if a supplement or extract has strong benefits, there's compounds in it that could be synthesized and studied directly. Nature occasionally gets lucky, but often pharmaceutical drugs can be more effective because they're targeted, standardized, and studied under strict scrutiny.

I speak in generalities, so this isn't always the case, but is more common than not with plant extracts. Something in that plant is having an effect, so either it has been studied and we know what it is, it doesn't really work, or its a worse version of something else we can synthesize.

I likely have a genetic predisposition towards high triglycerides and LDL cholesterol, and both my grandfathers had significant adverse cardiovascular events. I've taken several supplements to—hopefully—help keep my blood lipid composition in a favorable state: fish oil, garlic, L-Carnitine, spirulina, fiber supplements, CoQ10, and a few more. Yet, you know what works more effectively? Statins, ezetimibe, and PCSK9 inhibitors—all prescription drugs. Sure, they may have side effects, but so do supplements I've taken. In general, their safety profile is well-understood, and with consultations with doctors, most people can make informed decisions about them.

I still think supplements can nudge outcomes, but of the list of compounds above, I'm not nearly as confident that I get the outcomes I want as I am from their pharmaceutical counterparts. Supplements are often less targeted, so have a wider surface area of potential effects. Dosages are also all over the place — there's no standard to decide what a daily dose should be. You may be supplementing the right compound, but at doses far to high or too low for your intended effect.

To be clear: if you're deficient in something, supplementing it will likely help, assuming its in the right form. Vitamin deficiencies do indeed happen, and can surface very real health issues.

Berberine is frequently taken for metabolic health, and there's fairly strong evidence that it improves several markers for metabolic health. It's been taken for a long time as a traditional medicine and passes scientific scrutiny. Great, right? Well, its mechanism of action is similar to Metformin, a popular drug that treats metabolic disfunction. So, it's a natural form of a drug that's known to work? Largely, yes, but metformin has several known side effects, such as decreasing testosterone and potentially limiting the benefits of exercise. It's a useful drug (and berberine is a useful supplement) for a specific group of people—those with metabolic dysfunction—and potentially harmful otherwise. Or at least, it may not be as overall useful as we'd want for any specific person.

There's many supplements that help with glycemic control. Since I've had a limitless supply of CGMs, I've tested most that I could find. What works by far better than anything else? Acarbose, a drug developed for diabetics that may also improve longevity.

There's many supplements sold that claim to boost testosterone. Here's Examine's primary and secondary supplement recommendations to increase testosterone:

Whomp. Turns out if you're zinc deficient, supplementing can help testosterone. And there's evidence that DHEA can help some people. (This doesn't mean no T-boosting supplement will boost testosterone, but of the hundreds of compounds Examine has catalogued, none other are clear winners.)

I'm not arguing to just get on a bunch of prescription drugs. Rather, in my experience, the stronger the effect achieved on a supplement, the more the supplement isn't really supplementing anything, and is actually more like a drug. This is fine: we use many drugs to achieve specific outcomes. However, there's somewhat of a slippery slope of using "supplements" for a pronounced phenomenological effect and taking drug-like substances for the effects.

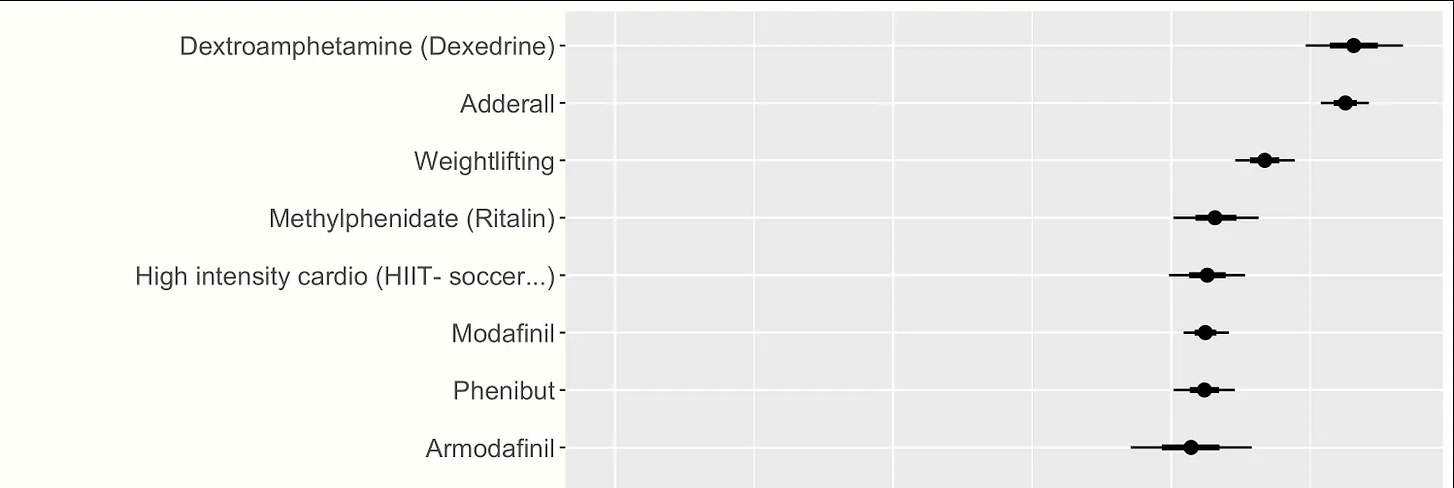

Nootropics are compounds that purport to help with cognition. A couple years ago, Scott Alexander polled his readers for what nootropics they've taken, and how well they "work". Not surprisingly, modafinil—a drug that treats narcolepsy—led the ranking, followed by caffeine and several other compounds that are either drugs, or were once developed as drugs. Troof replicated this, and many of his top nootropics are stimulants of some type or another:

From my own experience, modafinil works far better than any other nootropic that I've tried for cognitive improvement and technical work output, though with fairly consistent side effects for me (late day headaches). We shouldn't be too surprised. The best stuff looks more and more like drugs, or in this case, exercise (the best known drug?). This isn't necessarily a negative, but due to all the issues we've covered, the most targeted course of action to achieve an effect—whether that's to fix or improve something—is often the most direct route.

Why do supplements work so well?

I've presented a skeptical case for supplements: the quality of research is bad, you're probably not getting what you want, and there are probably more targeted ways to get your desired outcome.

Yet, we also need to contend with the fact that supplements work. Really well. Just read the reviews. People have ailments, try a few supplements, and find something that works. And often, it continues to work. Let's ignore the compound, and focus on the outcome that we can plainly observe.

I think it's a mix of these:

- People heal naturally.

- The act of trying to fix a problem or improve overall health has a causal relationship to the desired outcomes.

- Supplement use corresponds with high-agency, taking control of health and wellness, which corresponds to being healthier.

- Many ailments are not directly measurable, and subjective experience can be skewed by any proactive action.

- Spending money on an intervention biases us to believing in the intervention.

- Nutritional deficiencies are real and do happen. We may not commonly get scurvy anymore, but also eat pretty horrible diets overall.

- People who take supplements take a lot of things, and even with real measurable improvements, the underlying cause may not be isolated.

- People will keep trying new brands and supplements until things improve, returning to another one of these factors.

- Supplements can have physiological and phenomenological effects of varying degrees for individuals in a way that doesn't generalize to wider populations.

- Some things just work.

Several of these metaphorically rhyme with "the placebo effect", but that's unhelpful to understand what's happening. Instead, think of this as capturing an "intervention benefit". If taking supplements every day serves as a psychological conduit for agency that then helps someone exercise, then in a very real sense, the supplement "works". And many do indeed work in the classical causal sense, as well. Above all, wellness and health is personal. Since people respond to varying diets quite differently, it doesn't surprise me that people respond to varying supplements differently. Running studies that average populations can entirely miss this.

When you read reviews, it's near impossible to know which of the above ten potential influences was at play. Thus, reviews mean nearly nothing — we saw this with magnesium laxatives earlier. For many compounds, something is working, and we don't have the tools to isolate exactly what it is.

Making good supplement decisions

If supplements interest you, make sure you consume good research. Examine and ConsumerLab do some of the best research I've seen. I trust Peter Attia and Brad Stanfield's research and content. Unsurprisingly, both take relatively few supplements.

My main supplement vendors are Nootropics Depot, Thorne, and Pure Encapsulations. All are careful with ingredient sourcing, and provide lab testing results.

My personal consumption is primarily driven by self-experimentation and optimizing for my own goals, so I'm hesitant to publicly endorse any specific supplements. If you're curious, sign up for my email newsletter, and I'll share what has worked well for me.

For most supplement uses, I encourage being curious but conservative. Chasing the next great supplement can turn into an expensive hobby without much to show for it. Certainly, maximize whatever intervention benefit you can to feel great. But, Michael Pollan was spot in with his food rules, which I'll extend to supplements:

- Consume compounds you'd find in real foods. Most things that are beneficial are found in normal foods.

- Don't rely on them too much. Supplements can't fix poor diet or lack of exercise. Those are far more effective.

- Use normal, physiological doses. Dosing 100x+ what you could possibly consume from foods is unlikely to be beneficial.