Placebos

I want to let you in on a little secret: one of the best ways to improve your life is to try a bunch of things that probably won't work. The placebo effect is one of the most perplexing phenomena in modern medicine. It's a tool in for clinical trials, dismissed as a statistical artifact, and touted as proof of mind-over-matter healing. But what if our common understanding of the placebo effect is fundamentally flawed? Let's look at how rethinking the placebo effect as a complex interplay of expectation, context, and individual variability, we can unlock new approaches to improving health and well-being — approaches that leverage each person's individuality and belief without succumbing to magical thinking.

The Placebo Effect probably doesn't exist

The gold standard for clinical medical trials is double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled. We take an intervention, apply it to some people, and a fake intervention to others. It's science's "one weird trick" that can tease out causality instead of just correlation. And for this, I'm deeply grateful. It powers modern science.

We have to do the fake intervention to replicate the noise that we'd expect to see within a treatment group. Any effect found within the placebo group is, definitionally, not attributable to the treatment. Imagine giving a weight loss pill to a group of people (all 30-65 years old, overweight, live near one of your research labs, and are the kind of people who enroll in trials). It's not obvious what the default result would be for that specific group. So, when you give the pill, you also want to measure "what's the expected weight variation of this population?". Likewise, perhaps your pill has side effects, but without measuring what typical side effects are for your population, it's impossible to know if your treatment was the cause. (A rule of thumb: many people feel kind of crappy often.)

The placebo population outcomes are compared to the treatment outcomes to see how different they actually are. Sometimes, after tens of millions of dollars invested and years spent researching an intervention, this noise might mask whether there's a true effect or not.

One difficulty with studying interventions against placebos is that the population being studied actually matters. Let's suppose there's a form of psychotherapy that's highly effective for people who feel they need to produce to be valuable—that their external value comes from what they can do for others. Some of these people may be depressed, and burdened by the pressure to always perform to be good enough. However, if a study looked at this specific therapy on a general clinically depressed population, the result may not emerge from the noise.

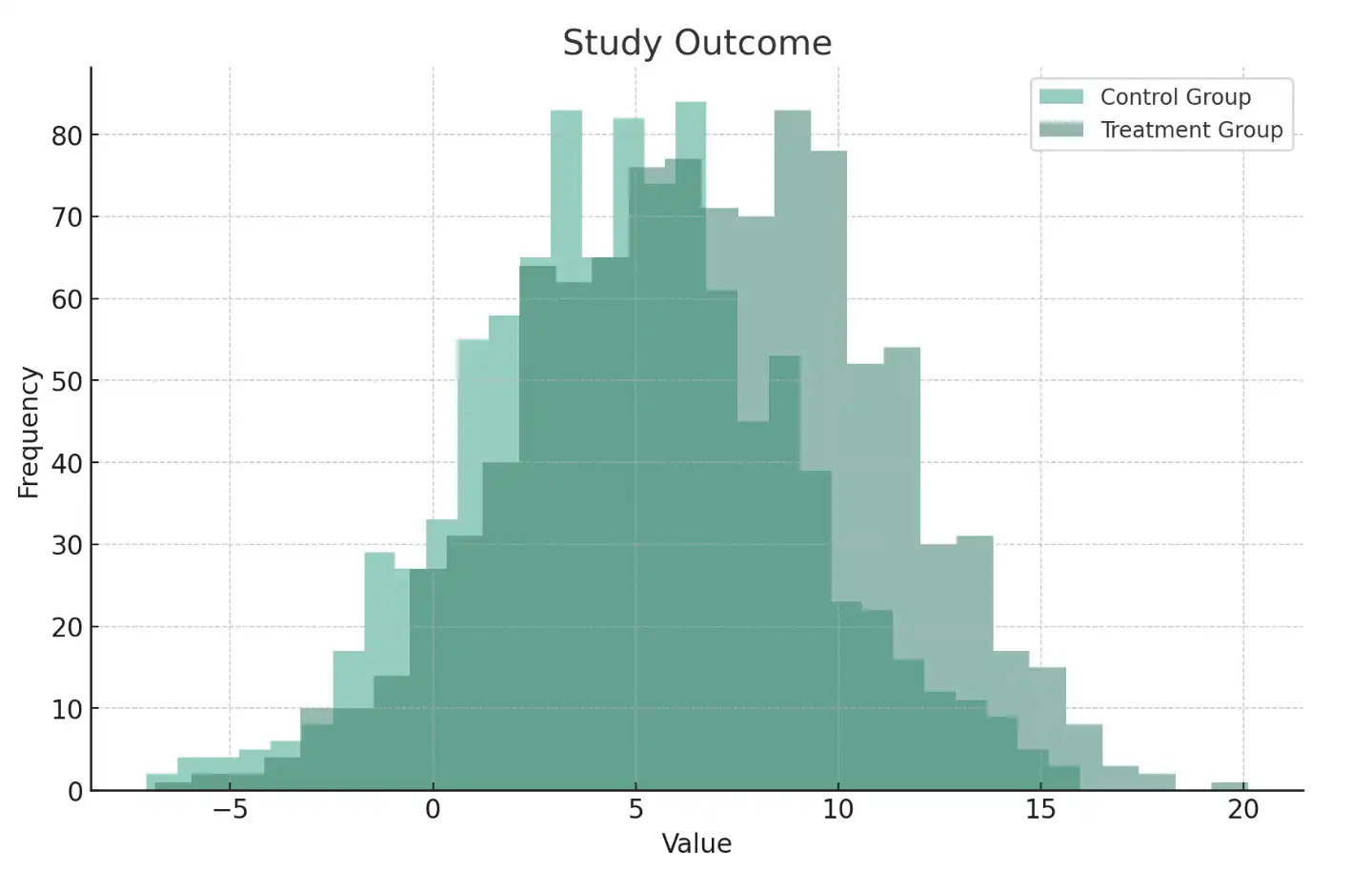

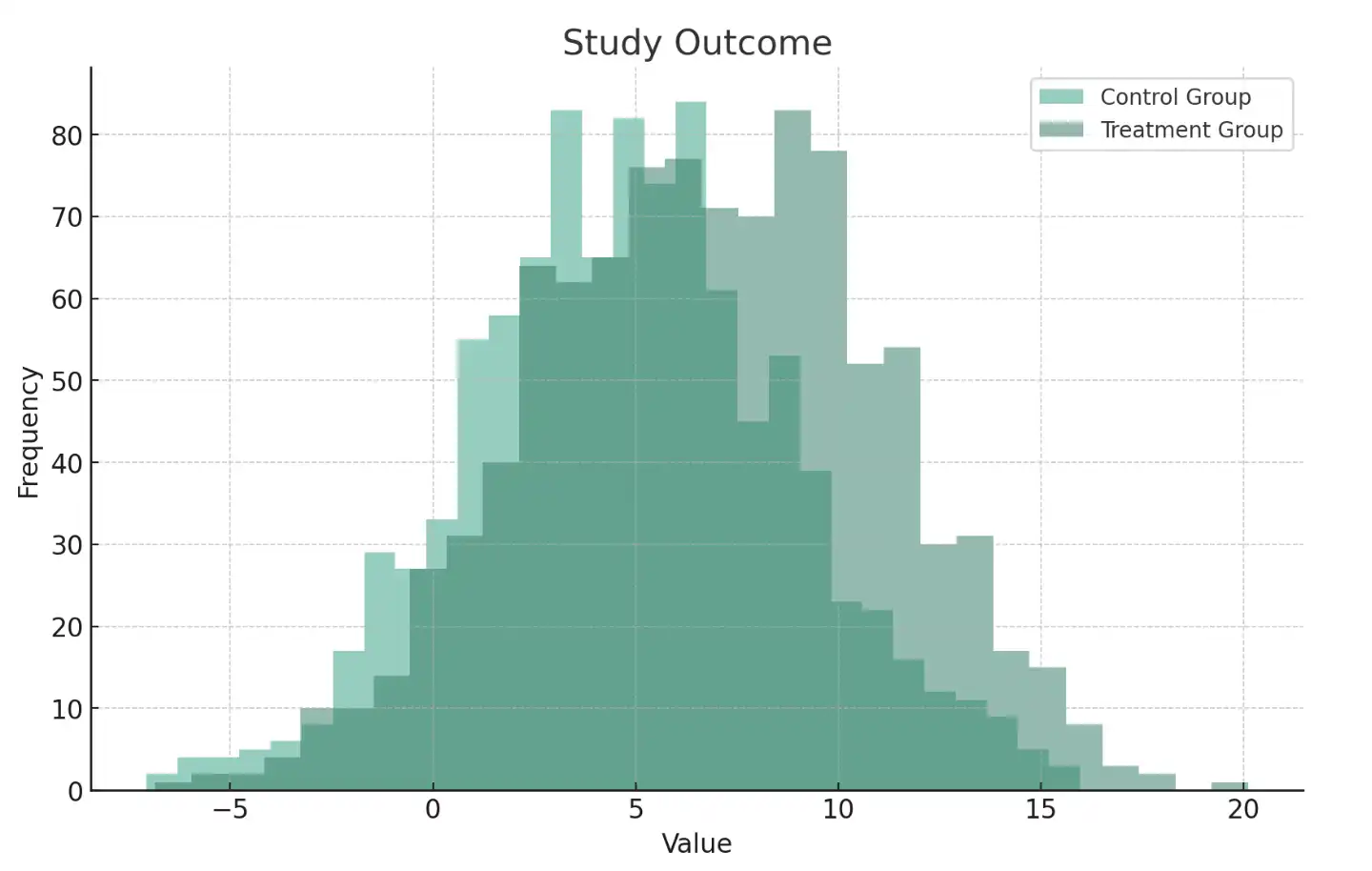

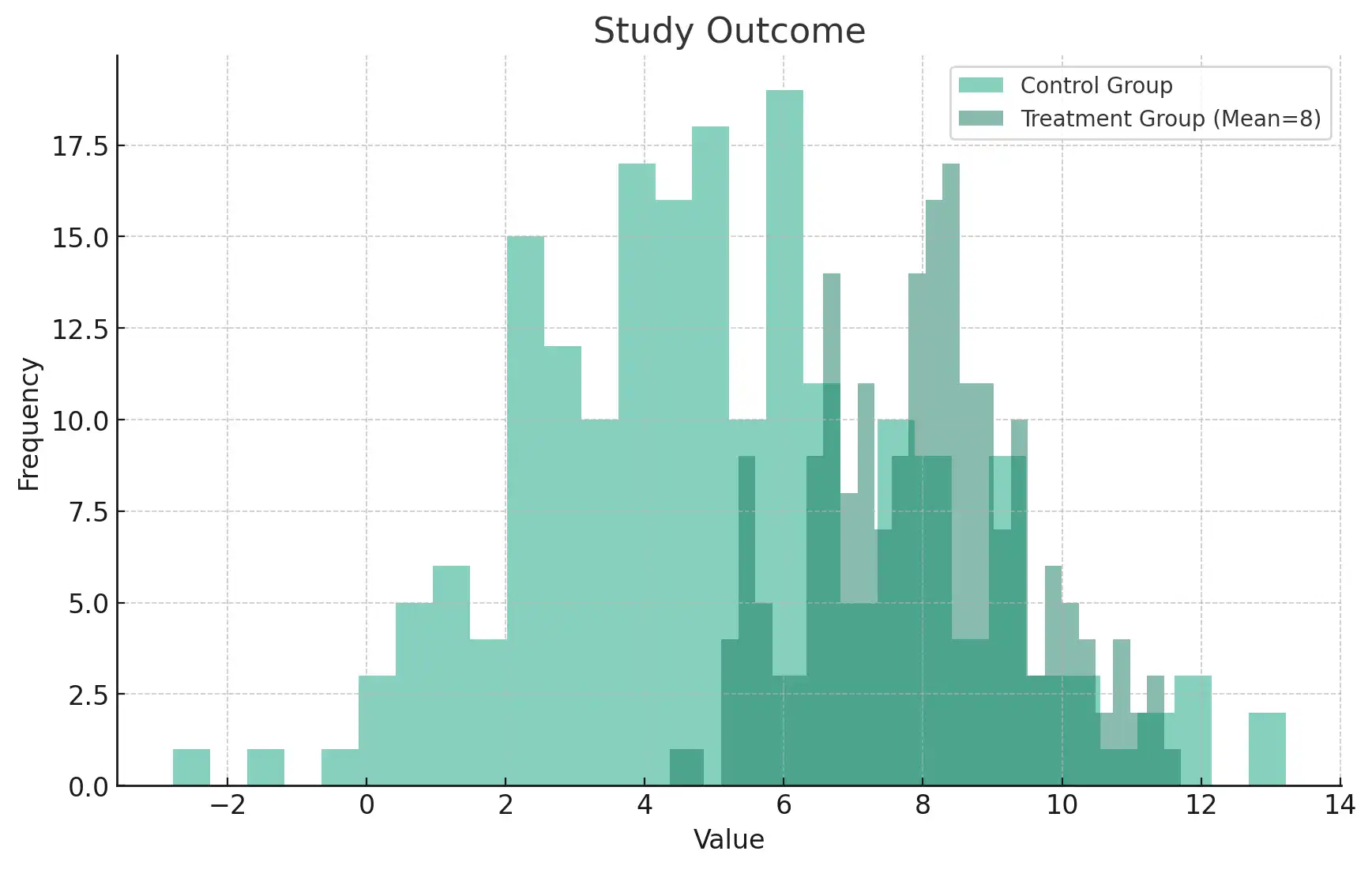

Let's look at the same study simulation from above, but where the original has a broad base population, and the revised study looks at a sub-population that responds better to the treatment:

Broad population study (small noticeable difference), vs targeted population study (large noticeable difference)

This has created an interesting selection effect in Western medicine. For illnesses that have specific, mechanistic causes that apply to large populations, we are pretty good at developing active treatments: the active treatments statistically beat placebos in trials. However, when something is more complicated or only works for some people, we do our best but often have nothing.

Why do we need to give a placebo, instead of just finding the right population and then doing no treatment? This is actually fairly controversial. The most straightforward, textbook answer is that whenever we recruit for an intervention group, we have a specific population. As discussed above, we don't actually know the expected distribution of outcomes for this specific population, so need to model it somehow. But, this doesn't explain why we need to fake a treatment.

The other answer is that the act of giving someone a placebo will influence their outcome, different from no treatment. Superficially, this isn't too hard to believe: if someone knows they're getting no treatment, they may act differently than someone who thinks they're getting treatment. But popular belief goes deeper: the placebo itself, somehow, facilitates additional healing that we wouldn't otherwise see.

When people talk about the "placebo effect", they're often pointing at this. And it's been studied a bunch. It seems to be getting stronger in the US, some placebos are stronger than others, and expensive placebos work better than cheap ones. We even blame people who are susceptible to the placebo effect for keeping new drugs off the market.

Is this even real? A meta-study from 2004 looked at several studies that included placebos and non-treatment groups and found the placebo didn't perform any better. Others have similar concerns:

... placebo effects compared to no treatment are small. Not just “small” in the meaningless sense of effect size, but too small to be noticeable or to make any clinical difference. For pain, a large meta-analysis found the mean placebo effect to be about 3.2 points on a 100-point scale, too small to matter. ... This is the case even though subjects in “no treatment” groups may have an incentive to exaggerate their symptoms in order to receive treatment, whereas those on placebo believe they are receiving treatment and have no such incentive. Still, effects are tiny, so tiny as to be meaningless in real life, and definitely tiny enough to turn out to be nothing at all with better methods.

— Against Automaticity, Science Banana

There are reasonable critiques of the 2004 study, however, with evidence that the placebo effect is stable. Fabrizio Benedetti, professor of physiology and neuroscience at the University of Turin Medical School, looked at the underlying data, and found that it suffers from selection effects, bias, and poor statistical analysis:

Aggregating without regard to the heterogeneity of disorders means we cannot discern whether a placebo really works. It is as if we wanted to test the effects of morphine across all medical conditions, like pain, schizophrenia, marital discord, asthma, nephritis, and other diseases. Of course a pooled analysis would find no effect of morphine. Another problematic aspect of Hróbjartsson and Gotzsche's study it that it is impossible to consider the critical factors involved in placebo responses, such as patient and physician expectations, the healing context, and the cues and factors that can influence the effectiveness of a therapeutic intervention.

— Placebo Effects: Understanding the mechanisms in health and disease (Benedetti, 2021)

So, what should we make of this? It's either real, a big deal, and getting stronger, or basically a statistical artifact of normal population behavior. Beyond statistical mistakes, perhaps the placebo effect only works on certain kinds of ailments, so when you look at everything, you don't see much benefit. Or perhaps modern researchers use bad placebos, and good placebos would most definitely show an impact. But what if there are actually several distinct things happening—several distinct placebo effects?

The Many Placebo Effects

Here are different things that I've noticed when they say "placebo effect":

- Natural population noise. People tend to get better, just get used to feeling bad, or drop out of studies. To look at a treatment's efficacy, we need to establish a noise baseline.

- Perception impacts subjective well-being. People feeling that a treatment has been given improves their subjective experience, which actually matters.

- Perception has a causal interaction with the healing processes directly. Stress, tension, etc might be actually hindering natural healing.

- Some things seem to work, for reasons we can't understand, in a way that also doesn't seem to replicate well in trials.

Any given example may be a mixture of these, but I think each is separate enough to be able to think about independently. The first two are the least controversial, and both have strong evidence supporting their reliable existence.

Most definitely: natural population noise exists and it's useful for us to model it. Some people get better, some worse. Overall, people tend to get better. There are many reasons they got better. Bodies heal, but also—even if you're in a trial—you may just try stuff. For depression, perhaps you've heard that walks outdoors help. Or perhaps you go see a therapist. Both placebo and treatment groups have this dynamic going on, so ideally the noise of each group is similar. Remember, for depression studies, these are depressed people who—ideally—would want to get better. It isn't a population of people whose behaviors are held static.

Perception also directly influences subjective well-being. Plainly, having a good attitude makes the day—genuinely—more enjoyable. This actually has impacts that are deeper than just smiling and pretending things are okay. Scott Alexander has seen it many times:

I want to add my own experience here, which is that occasionally I see extraordinary and obvious cases of the placebo effect. I once had a patient who was shaking from head to toe with anxiety tell me she felt completely better the moment she swallowed a pill, before there was any chance she could have absorbed the minutest fraction of it.

Here's my own story, showing how it also goes the other way: I recently had a fairly bad mountain biking crash. Riding a narrow trail in the Colorado backcountry, I hit a stump and landed about 15 feet away, hitting a sharp rock with my leg. Immediately, it hurt. Over the next few minutes, the pain improved. Then I noticed a little bit of blood on my shoe. Weird, I didn't realize I cut myself. Slowly, I removed my knee pad — and saw a large wound that ended up needing 30 stitches. A second, larger wave of pain came rushing in. When I saw that I was actually injured, I didn't consciously choose whether I wanted to feel more pain — it just happened. Scott Alexander, again, hypothesizes what may be happening:

Perceiving the world directly at every moment is too computationally intensive, so instead the brain guesses what the the world is like and uses perception to check and correct its guesses. In a high-bandwidth system like vision, guesses are corrected very quickly and you end up very accurate (except for weird things like ignoring when the word “the” is twice in a row, like it’s been several times in this paragraph already without you noticing). In a low-bandwidth system like pain perception, the original guess plays a pretty big role, with real perception only modulating it to a limited degree (consider phantom limb pain, where the brain guesses that an arm that isn’t there hurts, and nothing can convince it otherwise).

It makes sense that this effect likely is strongest on internal phenomena, like pain and mental states. Annoyingly, these are also the hardest to study, because they're all relative. Your scale of 1-10 may be different than your scale a year ago, and very different than mine. (Sasha Chapin recently explored how 10x happiness increases are possible, even though they don't typically show up in survey data.)

Let's consider the last two: perception can have a causal relationship with healing, and some things may work for unknown reasons. If you ask me, these are the most interesting!

With minimal controversy, there's some narrow room for perception to causally influence healing of cases where where tension, pain, and stress are actually contributing to the problem. Beyond that, the evidence is mixed — I've found studies that seem to support that this actually happens all the time and studies that say this effect is incredibly small if it exists at all. However, we do understand what's happening in some domains in a way that feels broader than "having a good attitude feels good":

The most productive models to better understand the neurobiology of the placebo effect are pain and Parkinson's disease. In these medical conditions, the neural networks that are involved have been identified: that is, the opioidergic–cholecystokinergic–dopaminergic modulatory network in pain and part of the basal ganglia circuitry in Parkinson's disease.

— How Placebos Change the Patient's Brain, Benedetti et al

If we open this further to "your conscious mind can influence things that most people would guess it cannot", we still find examples even outside of clinical contexts. I can give myself goosebumps through thought alone by imagining scraping a frozen popsicle against my teeth. I can also salivate by thinking of savory food and can increase my heart rate by imagining being chased. Does this count? Maybe. More interestingly, some advanced meditators can do even weirder things, like shut down conscious experience itself. And other meditators can, for all practical purposes, separate pain from suffering. So, while this may not be "people healing with their minds", perception can impact biomarkers wider than we may otherwise guess.

On the far end, can belief alone effectively fight cancer or heal heart disease? As in, can belief shrink a tumor or clear blocked arteries? I'm open to there being weird interactions possible, but probably not—at least in any meaningful way. When studies have tried to look for this kind of metaphysically-adjacent placebo effect, they generally come up empty.

We can imagine—however—a pathway existing that resembles "having positive belief lowers stress, and lower stress improves outcomes of real diseases". Or, "having positive beliefs induces higher adherence to treatment plans". If these and others were accurate, then we'd see a nice correlation between positive belief and outcomes. Likewise, simply telling people to be optimistic to heal faster probably wouldn't work, so we wouldn't actually see this effect if we looked at it directly.

This highlights an interesting web of causality: belief tends to impact many things, and those many things may change the environment sufficiently so that large outcomes could be observed. As we've seen, this is difficult to measure directly because we can't inject a belief into someone. We can make them think that the pill they took is maybe real, but that level of belief—and the associated other life changes it may be connected with—is quite different than someone who truly feels safe and secure because the crystal they're wearing protects them. And the person who deeply believes in the healing powers of crystals is fundamentally a different person than the general population.

Obviously, there are also things we have no plausible scientific explanation for. When I've talked to people about the mysteries of the placebo effect, this case is what many people mean, both positively and negatively. Some people believe the mind is nearly infinitely capable of healing. You just need to believe in the right way. Thus, in this model, placebos can facilitate powerful healing. Others think this is silly: the mind has quite limited ability to directly heal many diseases.

Fortunately, we don't need to rely on metaphysics or belief-transcending-all to start to understand how the placebo effect may be useful. We can bucket all of this noise, and start to critically think about how we might improve this process—whatever it actually is.

Why would placebos exist?

Let's take a step back, and think about why this effect might matter.

Imagine you're in pre-industrial times with an illness. You and your community want you to get better, but no one really understands what's wrong. By trial and error, some interventions have been discovered that "work". Perhaps you discovered that willow bark tea decreases pain. Or perhaps you have a ginger tea for nausea, which happens to contain 5-HT₃ antagonists that would indeed reduce nausea.

In general, though, there is no known "working" intervention—in the Western medical sense—for most ailments. Being pedantic, this means that you don't have access to targeted interventions for specific ailments that work on a population basis.

But, you don't actually care about that. You're sick and want to be better. Fortunately, there are a few things that work in your favor: people tend to get better over time and subjective experience is important. So, from your culture's observations, belief tends to affect outcomes.

I have some guesses as to why:

- Perception is a huge part of experience. Have you ever done something really difficult, but kept a good attitude and it wasn't all that bad? Or shifted to a bad attitude and things got perceptively worse? If we need to buy time for our bodies to heal, having tools to enhance our subjective perception does impact our experience.

- Perception goes deeper than we may normally assume. We like to think about how the mind is entirely separate from the body, but there are interplays happening that can't be easily sliced in a Cartesian manner. Kevin Simler collected several fascinating examples in Crazes, Fads, and Manias.

- Many ailments seem to have relationships between psychological and physical disorders. Many diseases highly correlate with each other, such as heart disease and depression. Perhaps addressing psychological needs can help with physical needs?

These all overlap and rhyme with each other. If all you have—ignoring a few targeted interventions discovered by luck—is what we now call the "placebo effect", you want to maximize that to the greatest extent possible. Whether it's to minimize suffering while natural healing happens or to induce physiological or behavioral changes that actually do help, your community develops and cultivates a rich ecology of practices that attempt to help people. You have no hard lines between illnesses of the spirit, mind, or body. Moral failings and physical failings may be seen as similar. Your viral infection may be seen as a demon.

We can think of these less as ontological claims about reality and more as a placeholder. From a reductionist sense, most of the models are mechanistically wrong. However, since belief matters, and more elaborate placebo practices might "work" better, your practices integrate all possible modalities. You use smoke and fire, loud sounds, bitter plants, community chanting, animal sacrifice, fasting, drums, and hallucinogens. Ramp everything up to 10. Big, bold, loud.

And, weirdly, it works. Or, at least, as good as it could—which may not be great, but is probably better than nothing. For some ailments like cancers, perhaps all the treatments do is make you feel better as you get sicker. For other things, perhaps they actually help the healing process. Over time, your community—through experience, trial and error, intuition, and luck—refines the practices to maximize overall success.

For you, whether it came from an intervention we now know that "works" or if it was just natural healing, they're one and the same. It's folk knowledge at its finest. Over time, the practices get refined to be better and better. Some even evolve into well-structured medical systems, with metaphors and abstractions that create cohesive healing models. Perhaps you're sick because your energy meridians aren't aligned: don't worry, we know how to help.

I'm neither saying traditional medicine practices are wrong, nor that they work in the modern Western medical sense. They're probably not random, though. Traditional Chinese medicine is, undoubtedly, incredibly rich. Practitioners aren't just making things up as they go along. Metaphors, such as "energy flows", evolve to capture some sort of true essence, even if the mechanistic model is false. They have a well-formed grammar of diagnosis and treatment, using models proven over time in a specific cultural context. (So, interestingly, they may not even port over to other cultures effectively.)

There's a common joke in Western medicine circles: What would we call Alternative Medicine if it worked? Medicine. Indeed, many alternative medicine practices may not be effective in any reasonable sense and can even be harmful. However, when Western practitioners talk about using "evidence-based treatment", it's both real and a strawman. It's real in that we want to use interventions that actually work. Obviously. It's a strawman because every practitioner wants this as well, but often uses different standards for establishing what works. All the professional "healers" near me who use plant medicines, sound baths, herbal mixtures, and energy work most surely care deeply about their clients, and also feel their practices use plenty of evidence.

Evidence-based medicine is actually more about claims about what constitutes reasonable proof: interventions that can be controlled for, we likely have a known mechanism for action, and have sufficient evidence that is observable across a population cohort. Western medicine is obviously fallible but does produce several highly effective and useful interventions.

In some fields, randomized controlled trials work quite well and there are many possible targeted interventions. This is especially true when we understand the underlying system or minimally diagnostic criteria directly connect to understood underlying conditions. As systems get more complex and mushy, we rely more and more on practical wisdom earned from decades of real-world experience.

And practically, we can't ignore natural healing and subjective experience. Western-trained providers regularly use placebos intentionally:

About half of the surveyed internists and rheumatologists reported prescribing placebo treatments on a regular basis (46-58%, depending on how the question was phrased). Most physicians (399, 62%) believed the practice to be ethically permissible.

— Prescribing “placebo treatments”: results of national survey of US internists and rheumatologists

Many practitioners also use placebos unintentionally, such as doing procedures that later are found to be ineffective, performing treatments that don't necessarily help better than placebos, or developing personal practices that yield results without clinical evidence. In actuality, Western medical providers use scientific knowledge but are practitioners. They do what seems to work based on their experience, and sometimes, trying different things is the best we can do.

Patients also actively participate in solving their health problems. They go to a doctor, who looks for signals that would lead to a root cause diagnosis and known treatment. This often requires guessing based on past experience. Perhaps the first visit fixes the problem. Perhaps it doesn't. The patient either stays with that doctor, who tries something else, or goes to another doctor, who tries something else. Eventually, sometimes, it "works": a targeted treatment is found, the patient naturally heals, or some intervention effect occurs.

In psychotherapy, there are many models of the human mind and how to best help people who are suffering. And many of these conflicting models work. Some therapies rely on looking deeply into body sensations to learn from parts of yourself that aren't normally conscious, under a model that your body contains wisdom that your mind does not. Whether this is true or not doesn't really matter to people this has helped. There are models of archetypes and parts. These don't have to literally exist to be useful.

A Systems Perspective

We want human bodies to behave like complicated systems, with separable components that can be tweaked and tuned independently casually. But instead, our bodies, society, and environment are complex systems.

Take a placebo for a headache, and you might feel a bit better, knowing that help is on the way. You may just be buying time for natural reversion to the mean.

More interestingly, placebos can also work by indirectly addressing a root cause. Many headaches are related to tension, so taking a placebo might make you feel better (for the above reasons), and feeling better may lift the tension — actually fixing the problem. We looked at this earlier, where the placebo may primarily be a psychological catalyst for behavior or environmental change.

Even weirder, this story about how ketamine fixed debilitating back pain rhymes with this line of thinking. The physician at the end acted dismissively because ketamine is a temporary anesthetic; it shouldn't "fix" anything. Yet, I find the author's beliefs of what actually happened entirely plausible. Let's imagine there was a weird nerve feedback loop going on: muscles were tight, causing a sensation of tension, causing muscles to tighten more, etc. What needed to happen was to break that neurological loop. Perhaps anything could have done it, like sedatives, other psychedelics, acupuncture, drum circles, crystals, or whatever. Different people probably respond differently to each of these, but using an anesthetic is not a bad starting place.

It's possible to be technically correct ("this treatment has no reasonable causal mechanism to fix this ailment"), and entirely wrong if we're looking at the problem the wrong way. Likewise, it's possible to be entirely mistaken about the mechanisms of a treatment, but accidentally right.

This idea of being right or wrong at the wrong layer of abstraction reminds me of the scene in Zoolander where they tried to get the files that were in the computer.

As it turns out, many ailments—being incredibly broad with what counts as an ailment here—have similar feedback loop processes. I was depressed for years and durably reversed it nearly instantly with a perspective shift—a new default basin of attraction. Unfortunately, I don't know how to replicate this for everyone, but do know it's possible, and didn't involve SSRIs or years of therapy (which work well for some people). Whatever happened with me would be near impossible to study, and might look somewhat like population variation in a study.

Within complex systems, causality is a web and far messier than we'd want. Feedback systems exist everywhere, and many large effects can be triggered by imperceptible stimuli. Furthermore, you can be right for the wrong reasons, as with "ineffective" surgeries that were performed for years that don't beat sham surgeries.

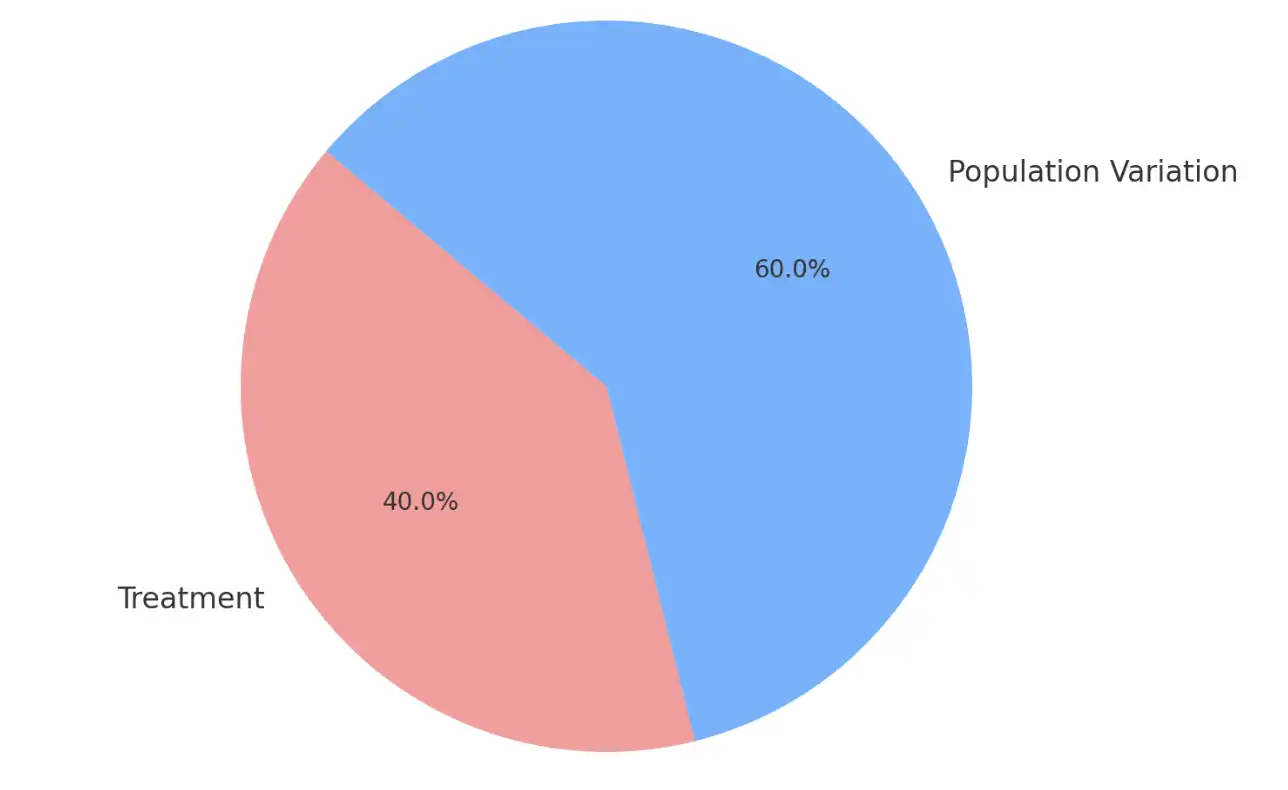

Science is doing a good job of understanding targeted interventions that work against well-understood populations. They should keep going—I'm alive today because of this process. But we should also be looking deeply at the "error term"—natural population variation—of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Imagine we could break down a healing effect like this:

Acknowledging how great the treatments are, why don't we—as a culture—take seriously the changes that we observe in population variation, to personally maximize outcomes?

We don't have a great name for explicitly maximizing the effect that is controlled by everything but the targeted causal interventions, so are stuck talking about "the placebo effect". When writing a study, this makes sense. When living in this world—like you and I are doing right now—it acts like every form of healing and feeling good that isn't science-validated is suspect.

It'd be incredibly useful if you could harness it, right?

Becoming a Placebo Adventurer

Some people can take literal placebo pills—knowing they're not "real"—and feel effects. Others functionally do this by consuming many ineffective supplements or undergoing surgeries that don't actually do anything.

I used to carry around of big jar of placebo pills to change my mood to whatever I wanted After a while I got tired of imposing my will on myself. Sometimes the body & unconscious machinery knows better than “you” what mood you ought be in

— @TylerAlterman

We want what I call a placebo pump: a mechanism that encourages and fosters the placebo effect to the greatest extent possible. To the extent that we can, we want to do our "proven" targeted interventions in a context that also elicits as much extra improvement as possible.

In practice, this means trying a bunch of things. Most ailments take time to heal, but there are many reasons that actively participating in the "solving what's going on" process helps.

First, we want interventions that maximize our chances of getting lucky. There's a lot we don't understand, and sometimes just trying things can fix problems for reasons we wouldn't be able to predict. Elizabeth Van Nostrand calls this luck-based medicine. These interventions are not always simply noise—they may be directly and literally exactly what you need.

Each of us isn't a population average, but populations get studied. Study populations serve as useful priors—what should we expect?—but things may "work" for you that don't work for people in general. For a simple example, if you have a Vitamin C deficiency, taking it will indeed help. However, if you have no deficiency, there's likely minimal benefit. If we ran a study "does taking Vitamin C improve overall health?", on a population basis, we'd likely see no statistically significant improvement. Likewise, if you see a study that shows how treatment for people who are clinically depressed only slightly helps people, you don't know whether you'll experience any change, slight improvement, or massive improvement. All are possible.

Recommended treatments are optimized for populations, when each person may not be represented by the population well. Some people are willing to do intense interventions to fix ailments, while others are not. Lean into your own quirks and personality.

Furthermore, even if the intervention wasn't exactly what you needed, many woo-adjacent treatments that work are often right for the wrong reasons. They purport a specific model of the world that isn't literally true, but functionally is useful. For example, Dr Sarno has a very specific model of back pain that may or may not be actually true, but it doesn't actually matter: his method observably works for many people. (Seriously, read the Amazon reviews of his book.)

So, without exaggeration, become an explorer and try a bunch of stuff. Be curious, and pay attention to your own felt sense. Optimize for trying things that feel good. For example, I get occasional afternoon headaches and cold plunges fix them nearly every time quickly. I have no idea why and have no confidence they'd work for everyone. But for my body, specific headaches, and personality, they work.

Perception and subjective experience matter a ton. Beyond just being optimistic, belief has causal effects on several internal systems that you may not expect. From Fabrizio Benedetti, mentioned earlier:

First, as the placebo effect is basically a psychosocial context effect, these data indicate that different social stimuli, such as words and rituals of the therapeutic act, may change the chemistry and circuitry of the patient's brain. Second, the mechanisms that are activated by placebos are the same as those activated by drugs, which suggests a cognitive/affective interference with drug action. Third, if prefrontal functioning is impaired, placebo responses are reduced or totally lacking, as occurs in dementia of the Alzheimer's type.

— How Placebos Change the Patient's Brain

To the extent possible, get out of bad attractor basins. For mental health, there's a large menu of modalities that work well for some people. Some treatments that seem to only work barely better than placebos may be lumping together dissimilar people. For a large group of people who suffer from depression, there may be many separate causes, each that responds better to something else. Cognitive behavioral therapy, Internal Family Systems, somatic therapies, psychedelic therapy, getting into exercise, changing diets, SSRIs, and so forth all help some people. Keep trying things.

Scott Alexander has noticed this idiosyncratic, unclear-causal-chain outcome after skeptically looking at the concept of trauma being stored in the body:

[Update, written a few weeks after the rest of this post: maybe it is all wizardry. I recommended this book to a severely traumatized patient of mine, who had not benefited from years of conventional treatment, and who wanted to know more about their condition. The next week the patient came in, claiming to be completely cured, and displaying behaviors consistent with this. They did not use any of the techniques in this book, but said that reading the book helped them figure out an indescribable mental motion they could take to resolve their trauma, and that after taking this mental motion their problems were gone. I’m not sure what to think of this or how much I should revise the negative opinion of this book which I formed before this event.]

— Book Review: The Body Keeps the Score

In other words, whether or not trauma is stored in the body misses that for some people, adopting this model seems to actually work. Was it new optimism? Or something about that model actually works for them? Or perhaps a general reversion to wellness? We won't know.

Pay attention to what changes your behavior in other beneficial ways. For example, I find that when I take a morning walk in the sun, I feel better—but also tend to do other healthy things such as eat better, go out again in the afternoon, and socialize more. The morning walk may not literally cause those effects, but it contributes to an environment where I get more of what I want. Many athletes exploit this regularly:

When trying things, give it a real go. Part of the effect may be limited by your perception, so while you should be reasonable, it's useful to actually lean into it. Because of this, pick low-risk things. We're complex systems, and taking a slew of poorly supported supplements can elicit some pretty gnarly side effects. I know someone who did over a dozen cognitive enhancers at the same time at once, which threw them into a sort of stimulant-driven temporary psychosis. Eeesh.

Have a clear goal. Rationally-informed people like you and I can learn a lot from people who believe in manifesting. Not that manifesting "works" in a quirky metaphysical way, but... maybe it works practically? One of my favorite exercises is to actually write out what I want, what my hell yeah!'s are. This process helps make those goals legible in a way that they may have not been before. Most health and wellness interventions are pretty random, and many are silly. Active interventions are like books: if they hit you at the right time and take you where you want to go, they're awesome. Otherwise, they're a bit pointless.

Don't neglect the recommended course of action for anything serious. But if Western medicine is maximizing the "treatment" effect, it's your job to maximize the effect from everything else. Find your own effective placebo pumps.

There's beauty in being an active participant in explorations to get better or feel great. Even if life obeys deterministic naturalist laws, we understand so little of the natural world, so we make relevant approximations. Our culture needs to re-build technologies that maximize the sort of population variation that we call the "placebo effect", no matter what's causing it. Perhaps over time we'll learn more, and develop incredibly strong placebos that complement targeted medicine. Until then, stay curious and have wonder. Find silly rituals that work for you.

With that, excuse me while I dip into cold water.